KAKUMA, Kenya—A sea of 76 students in bright violet uniforms with pointed white collars confronted Jessica Deng as she stepped into her classroom. The students – all girls in the eighth grade – crowded around worn wooden desks and battered textbooks as she briskly set them to work on a math problem calculating the speed of someone who travels 80 kilometers in 4 hours. The equatorial sun had begun to heat up the September day and burned through the curtainless windows of Deng’s classroom at Bahr El Naam Primary School, a compound of dusty one-story cement rooms lacking air conditioning and electricity in the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Northern Kenya.

Deng is just 21; her students are only a few years younger than she is. Standing tall in a black T-shirt and gray slacks, a braided bun on top of her head, she carries a red pen as she walks up and down the aisles. The girls watch her pass with eager eyes and wave their notebooks for her to correct. Deng is a role model, having both a high school diploma – earned at a boarding school in Nairobi, no less – and a job. She tries to embolden them to dream big.

They do. Some want to be lawyers or doctors. One wants to be a pilot. But for most, the obstacles that stand in the way of achieving these ambitions are insurmountable.

Deng herself wonders if she will reach her goals. She wants to go to college in another country to study public health. She’s applied for a scholarship to a university in Canada that would take her away next year. But it’s highly competitive; she’s already been rejected twice, and this was the last time she’d be allowed to apply.

“My students, myself, every other girl or woman that is in the camp, if all of us were given the opportunity [to get] quality educations somewhere else, we would lead better lives,” Deng says. “We would go back to our homelands and change some things.”

These young, resilient girls are an untapped resource. But they’re at risk of being indirect casualties of entrenched conflicts, their potential squandered in underfunded schools and wasted by lack of opportunity. Investing more in their education and increasing their post-high school options would give these young women, and thousands like them, the chance to improve their lives and the lives of others.

For now, Deng and her students are stuck, along with 185,000 other refugees, in Kakuma. It’s a purgatory where most people depend on the subsistence rations passed out by the U.N. for survival. They are barred from working anywhere outside the camp and must search for jobs within the small economy that has sprung up—running makeshift marketplace shops selling soda or shoes to other refugees or working for aid organizations.

Related: STUDENT VOICE: ‘Then one day a bomb exploded during my geometry class’

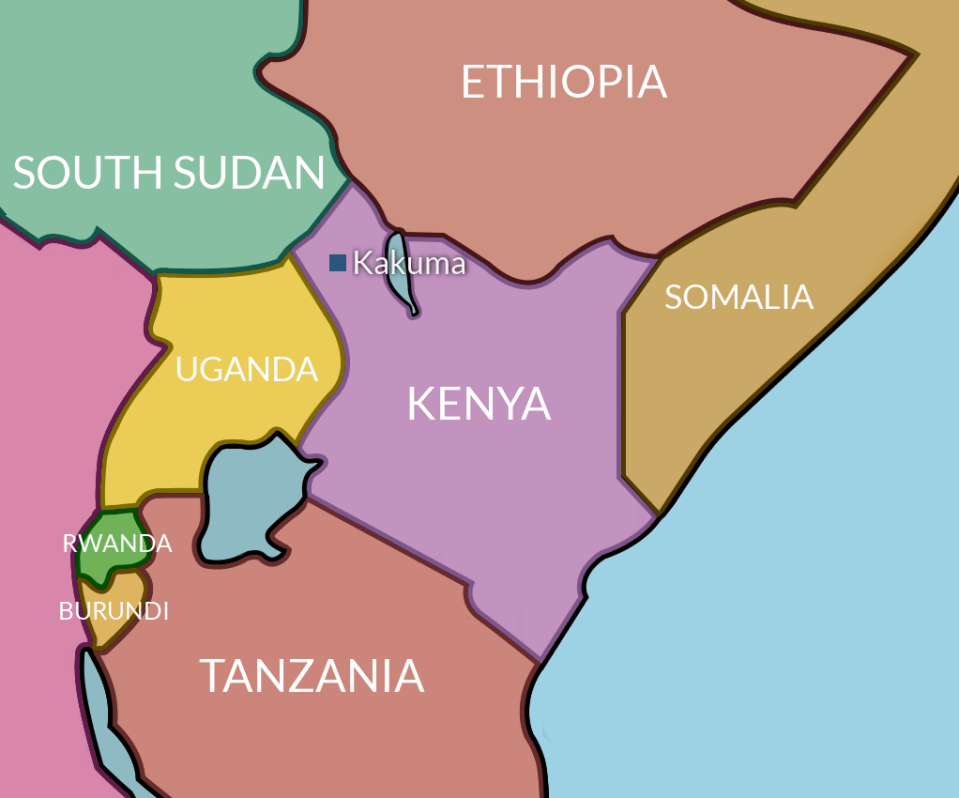

Career options are limited, but so are chances to leave. Kakuma’s refugees were driven from their homes in countries like Somalia, Ethiopia or the Democratic Republic of Congo by war or famine. The bulk of Kakuma’s residents are from Sudan and South Sudan, a part of the world that has been in almost non-stop conflict since the first Sudanese Civil War began in the 1950s. Going home is seldom a realistic option. Resettlement in another country is a long and difficult process that less than 1 percent of refugees ever achieve.

The United States resettles more refugees than any other country, but the number allowed in has been decreasing steadily since President Donald Trump took office. In 2016, the United States welcomed 84,994 refugees, just six shy of its cap. In 2017, it took in fewer than 54,000 and, in 2018, officials reduced the official cap to 45,000 and as of November had taken in about half that number. In September, the Trump Administration proposed lowering the cap further to 30,000.

The Trump administration has defended the reductions in part by arguing that refugees don’t want to come to the United States; they want to go home. That’s not entirely wrong. None of the refugees I meet during a week reporting in Kakuma mention coming to the United States. Many talk instead about returning home and working to rebuild once violence subsides.

But when I ask what they wish outsiders knew about their lives, most say they want people to understand that Kakuma is an exceptionally tough place to live. They stay only because they have no other options. Many students get upset talking about their education, frustration showing on their faces as they repeat their complaints again and again. They don’t want much: A light so they can study at night. Smaller classes. Access to computers.

“More than 50 percent are not living how they wanted to live,” Deng says of her students. “They want to get out.”

While they try to stay motivated by focusing on the chances—however slim—of getting home, or anywhere else but here, many are also resigned to the difficulties of their lives and how little power they have to change their fate.

One day I see a girl unconscious after she fainted during a break between classes. The school doesn’t have a nurse. Instead the girl’s friends carry her into a space between two buildings seeking some room and shade. They gather around, fretting and shaking her. The scene escapes the notice of most students and teachers. The teacher I’m talking to checks in and tells me the girl has been fainting regularly lately, but she’ll wake up. There’s nothing else to be done.

The harsh reality here contributes to low school enrollment among refugees, particularly girls, that only gets worse as they get older. Forty percent of primary school students in Kakuma are girls, but they make up less than a quarter of all secondary school enrollments. That’s despite research that shows educating girls can have large positive benefits for society: child marriage and child mortality rates drop while female earnings go up.

In the camp and elsewhere, agencies work to change cultural beliefs that girls don’t need to be educated or should be married off as teens to the highest bidder. Programs have begun to make progress increasing female retention in school. But a lack of resources makes it hard for these girls, and other displaced children, to capitalize on the slowly shifting attitudes.

Related: Refugee students languish in red tape as they seek to resume their educations

Nearly 20 million refugees live under the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) mandate, more than half of whom are under the age of 18. More than a third of those children and teens don’t even attend school. When they do, their schools are chronically underfunded. In 2015, the United Nations humanitarian appeals called for $531 million for education. Only $100 million was received, according to a 2016 report by the Malala Fund. The report also found that refugee education projects received less than 1 percent of all global education aid in 2014.

Schools in Kakuma operate on a shoestring budget. Windle Trust Kenya, the nonprofit that runs the camp’s secondary schools in partnership with UNHCR, lacks the funding to do more than triage the situation. It spends $1.47 million annually on the schools – or $153 per pupil. (By comparison, per pupil sending in the United States tops $11,000.) That’s not enough money to reduce class sizes that frequently surpass 100, make sure every student has access to textbooks, or bring adequate mental health services to campuses to help students deal with trauma that so often gets in the way of learning.

Young women here, like Deng and her students, know full well the obstacles they face. And yet they get up each morning and make the trek to school on foot, trying to ignore the jeers of the men around them and the indifference of most of the world to their plight, hoping they might be the one to get out. Leaving Kakuma for high school, “gave me the opportunity to realize who I was and what I could do, other than just being a refugee and staying in this camp,” says Deng.

“It sometimes breaks our hearts that you’ve trained them, but at the end of the day they’re still in the camp,” says Kakuma’s Greenlight Secondary School Principal Robert Bett. “Their lives haven’t changed.

Crowded primary schools

In 1991, Kakuma was just a small town in a barren part of Kenya. But the camp was established as a UNHCR location in 1992 when thousands of refugees – including the orphaned Lost Boys of Sudan – began arriving. Soon, more refugees poured in from Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan.

Deng’s parents were among those who came to Kakuma to escape the civil war in Sudan. They don’t tell Deng much about what drove them from their home, and she doesn’t ask. When they arrived in 1992, refugees were creating a makeshift city of tarp and mudbrick homes with dirt floors. These small dwellings covered a landscape previously dotted with the one thorny tree stubborn enough to grow in the cruel conditions here.

More and more homes were constructed. By 2011, when South Sudan declared independence, about 82,500 refugees lived in Kakuma, about half of whom were Somalis who had escaped their own civil war. In South Sudan, fighting among tribes continued and brutal civil war broke out again in 2013. (A recent report estimates that more than 380,000 people have died so far in that conflict.) By 2014, Kakuma was 58,000 people over capacity and the UN created a new settlement just north of the camp to accommodate those continuing to flee.

These tens of thousands of people with nowhere else to turn have opened businesses in the camp’s many market places: barbershops and butcheries, pool halls and phone charging stations. They’ve joined the camp’s hundreds of sports teams. And they’ve raised families.

Related: Will high school segregation for refugees lead to better integration?

Deng was born at the camp in 1997. In some ways, growing up in the camp – surrounded by a variety of cultures as well as fellow South Sudanese refugees – was exciting. “But at the same time, it was not easy,” she says. “I didn’t get everything I should have gotten as a child.”

Refugees rely on UN disbursements for most of their food – they eat the same thing over and over again and there isn’t always enough to go around. On each block, there’s one water tap where people line up daily, holding empty jerry cans to fill.

Hospitals are overcrowded, and a visit often results in a handful of painkillers. Many refugees have faced severe trauma, but there’s little in the way of mental health care.

Most days, the sun is hot and unforgiving. But when the rain comes, it often floods the camp and washes away homes. Refugees have no choice but to rebuild and rebuild again. It happened to Deng’s family “all the time” when she was younger, before they were able to move to higher ground, she says. “We’d have to come back again and [build] it again because there’s no where we can go,” she says.

She attended primary school at Bahr El Naam, the same all-girls school at which she currently teaches. She sometimes had a hard time paying attention in the overcrowded classrooms. The din of dozens of students packed in the room meant she sometimes “couldn’t even hear what teachers were saying.”

Although the physical conditions of Bahr El Naam have improved since Deng was a student – better buildings, more trees, a contiguous fence so students can’t skip out during the day – many of the problems remain. The UN aims to have a 40-1 student-to-teacher ratio in its schools at refugee camps. In Kakuma, there are more than 95 students for each teacher. I visit one classroom that has more than 200 students on its rolls, leaving the teacher only a few square feet in which to stand.

There aren’t enough textbooks or desks. Students in the early grades must sit on the floor.

And that’s despite the absenteeism that plagues Kakuma’s schools. Deng has 160 students on her roster, but says at least 40 are absent each day. When it rains and the seasonal river bisecting the camp fills, many students – and teachers – can’t make it in. On days when the UN gives out food or firewood, attendance dips. One teacher tells me he always has to reteach the disbursement day lesson the following day. Some students routinely miss half an hour of afternoon lessons because they have to walk so far to go home for lunch.

Other students don’t come to school because chores or money-making opportunities draw them away. Some skip because they don’t see the point in going.

Teachers are also difficult to recruit and retain. About 85 percent of teachers are refugees themselves, most of whom have gone to school at the camp and many of whom begin teaching without any formal training. The only qualification necessary is a high school degree.

Related: A racially charged assault spurs schools to rally behind Portland’s large refugee community

Deng fell into teaching without any real enthusiasm shortly after finishing secondary school. She wanted a job and there are few other options. As a teacher she earns about $74 a month.

At first, she struggled to manage her students. But then she signed up for a training program called Teachers for Teachers. (Disclaimer: Teachers for Teachers is run by Teachers College, Columbia University. The Hechinger Report is an independent unit based at Teachers College.)

The program, which has now reached an estimated 90 percent of primary school teachers in Kakuma, taught her how to control her classroom and keep her students’ attention. It also helped her grow to love teaching. “When a girl understands mathematics – and I had trouble getting maths in school – but when I teach and somebody understands, it feels nice,” she says.

Navigating secondary school

Deng’s family was able to pull together enough money from relatives to send her to high school at a boarding school in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi. (In Kenya, boarding schools generally offer the highest quality education.) Deng recalls her mother saying, “I’m not educated, but if I was, we wouldn’t be living like this. So it’s your turn to be educated and not live like this.”

Many men in the community scoffed at the idea that Deng would go away to study, telling her that girls were stupid and she would drop out.

Deng was tempted, as she struggled with subjects like chemistry and geography and the intense pressure to do well on tests. One time, she failed an exam badly, despite studying hard, and came to her teacher crying. “I wanted to go home,” she says. “I told her I was very discouraged … I rather would stay at home than get such results.” Her teacher talked her down.

She never forgot the naysayers. “It was my drive,” she says. “It’s what made me actually complete my secondary school … I did it for myself, but I also wanted to prove others wrong.”

Looking back, Deng says her parents were right to send her away, even if it meant only going home once in four years. “They knew what I would turn out to be if I continued learning [in the refugee camp],” she says. “I would not be who I am right now.”

The five secondary day schools in Kakuma face many of the same problems as primary schools. The classrooms are overcrowded; students sit four or five across at wooden desks designed for three. Students share textbooks among as many as eight other pupils, which makes it hard to study after school. Schools don’t have the money to do all the science labs in the curriculum.

Last year, in an attempt to balance the budget, Windle Trust and UNHCR introduced secondary school fees. Unless students receive a scholarship, they must pay $30 per year. Multiple students I speak with say they worry about how they will be able to pay, but Windle Trust officials say the organization has plans in place to identify students who can’t afford the fee and provide them with scholarships.

Related: How trauma and stress affect a child’s brain development

Had Deng not gone to boarding school, she likely would have attended Kakuma Refugee Secondary School. Opened in 1992, it’s the oldest of the secondary schools at the camp and enrolls more than 3,000 students. Because of space issues, one group of students comes in the morning and the other comes in the afternoon.

On a Monday morning in September, the Kakuma Refugee Secondary School teachers sit around a handful of desks in mismatched chairs for a meeting in the staff room. Many had just arrived over the weekend, despite the fact that school had started the previous week. The contract with refugee teachers had lapsed after the previous term and funding problems had prevented the Windle Trust from getting everyone back in the classroom immediately.

As the teachers attended their meeting, students are left on their own in the classrooms to study for a start-of-term exam the next day. These test are given at the beginning of every term, partly to encourage students to study over the break and partly to help teachers gauge where their students are academically before diving into lessons. Some students sit with their notebooks out and peruse their carefully written notes. Others look at tattered copies of thin textbooks. Many chat or wander about the grounds.

The classrooms are nicer than the cramped mudbrick buildings that used to line the school’s two courtyards. Now, the rooms have high ceilings and metal walls painted bright blue on the outside. On the inside, there’s the occasional decoration – a poster of the periodic table of elements or a ripped map of Kenya.

What appear to be directional signs extending from a pole at the center of one courtyard turn out to be directions of a different kind, displays of the school’s core values: integrity, efficiency, patience, punctuality, respect, professionalism and humility. Staff hold twice-weekly assemblies in the other courtyard, in which rows of benches sit in the direct sunlight. The principal wants to cover this space, one of his many plans, which also include rebuilding the staff room, expanding the number of classrooms and planting 2,500 trees.

Marie Jeserine, a 20-year-old in her third year of high school, easily lists other changes she’d like. She wants a bigger library and more latrines (the school has 18 right now for 3,000 students, although an additional 16 are under construction). She’d also like school buses. Jeserine walks 50 minutes to get to school. By the time she arrives, she’s already tired.

In fact, she’s often tired before she even sets out. Her father has mental health issues. “He normally disturbs us during nighttime so we don’t sleep,” she says.

Sometimes he tells her to stay home: “Since you will stay here in the camp, you have gained nothing so you should not go to school.” By the time she enters the crowded classrooms, she has trouble concentrating.

Related: A little girl’s school helps her deal with trauma at home

Like Deng, Jeserine was born in Kakuma and she sometimes struggles to remain hopeful about life after high school. It’s helpful to meet with the school counselor. “[She] tells me not to give up, that there are many things in the future waiting for me,” Jeserine says. Attending university is one of them, she hopes.

The secondary schools in Kakuma share two counselors between them, paid for by the Kenya Equity in Education Project, or KEEP. (Teachers and students are also trained in counseling and peer counseling.) The program, run by World University Service of Canada along with Windle Trust, is a broad effort to improve girls’ education in Kakuma and at Kenya’s other refugee camp in Dadaab. KEEP holds remedial courses on Saturdays and over school holidays. It provides scholarships and supplies to the girls and gender-responsive training to schools. The efforts have improved enrollment, attendance and literacy rates for thousands of girls.

An escape from camp chaos

The year before Deng graduated high school, a new option opened up right along the edge of the camp: the Morneau Shepell Secondary School for Girls, the first refugee boarding school in the world. Now, a relatively small group of girls (352) benefit from the most intensive intervention to improve female education at the camp.

Martha John Korok, 19, is one of them. She’s among the thousands of South Sudanese driven from their homes in the last decade. Her family first tried to outrun the violence without leaving the country, moving from place to place. But Korok remembers the gunshots each night. In South Sudan, “you can’t spend a night without a bullet,” she says.

Her family heard about a safe haven in Kenya, and in February 2013, they fled on UN transport to Kakuma with nothing but a few possessions.

Korok thought the camp would be like a real city, fully developed with “lights all around.” Instead, she saw single-room shacks, dust and fences. There were fences everywhere. “I thought maybe they were keeping cattle,” she says. “It was all about human beings.”

She enrolled in primary school, where she watched many of her female classmates drop out. She had to ignore the boys who felt threatened by her and told her a girl couldn’t do well academically. “You’re not supposed to be higher than them,” she explains.

In September 2013, her father unexpectedly passed away, after seeking help for a headache. Korok blames the health care providers. Her uncles back in South Sudan tried to convince the family to return so they could arrange a marriage for her. Her mother ignored them and the uncles stopped sending her family money.

The whole ordeal strengthened Korok’s resolve to do well in school. She had a new dream: She wanted to become a doctor and prevent what happened to her dad from happening to others. So when she got the chance to attend Morneau Shepell, she took it.

Related: Unaccompanied minors bring hope, past trauma to American schools

Girls who perform well enough on their exit exam from primary school are invited to apply to the school. From there, school officials work with the UNHCR to determine which girls need protection the most – which ones are at risk for forced marriage or violence at home, are in single parent homes or are orphans. For the 2018 school year, there were 1,000 applications for 90 spots. Eighty percent of the students are refugees, and the rest are Kenyans from the surrounding area.

Principal Irene Kinyanjui says that every morning at the start of a new term as many as 20 girls show up asking to be enrolled. But she must turn them away. A self-proclaimed “polite notice” on the deputy principal’s door announces “there are no vacancies in all the classes.”

At Morneau Shepell, the girls live in an educational oasis set away from the chaos of camp. They don’t have to face men who demean their goals, or worry about assault on the walk to school. They have electricity (unless it’s too cloudy for the solar power to work well). The classes are relatively small (around 40 students each) and are full of laughter.

When classes finish, students meander in groups to their dormitories to change from their plaid skirts and teal Morneau Shepell T-shirts into colorful sundresses. They gather in the dining hall on weekends to hold dance parties or watch movies on the school’s small flat screen television. Some girls are married; their husbands can come to visit, but the girls can’t leave campus during term.

Morneau Shepell, the Canadian-based human resource consulting and technology that funds the program, opened the school that bears its name after learning about the barriers girls face attending day schools at the camp. In 2016, the firm pledged more than $1 million over five years to the school, which costs $700 per pupil to run each year, including teacher salary, dorm supplies and security. Yet even this school lacks resources. There aren’t enough textbooks or supplies for all students.

Still, Korok remains grateful that Morneau Shepell has provided her with a refuge within the camp and allowed her to focus on school, giving her a fighting chance for her future. A future that she, like Deng, has pinned on Canada.

Dreaming of Canada

In Kakuma, going to Canada is the holy grail of post-secondary plans. Girls at Morneau Shepell have a shot at a scholarship to the University of Toronto. They must meet minimum requirements on the end-of-high-school exam and go through an interview, although not everyone who qualifies gets in. Last year, fewer than 10 of Morneau Shepell’s 70 graduates earned a spot at the university.

Still, their odds are better than those students from other Kakuma secondary schools, who must try for a scholarship run by the World University Service of Canada (WUSC). It allows refugees living in five countries, including Kenya, to resettle and attend a university in Canada.

Related: A Yemeni family flees a war-torn nation and bets on a future in rural Appalachia

This is the scholarship Deng has applied for three times. Canadian universities—both public and private—waive tuition and accommodation fees for refugee students. Any additional money needed to support the students comes from small fees paid by their Canadian classmates. A set amount, ranging from 25 cents to $20 per student, is collected by the student union.

WUSC is actively looking to replicate the scholarship program in other places, including the United States. Michelle Manks, the organization’s senior manager of Durable Solutions for Refugees, says that they’ve found schools that are interested, but need to figure out logistical barriers in the immigration system.

In 2017, more than 2,000 students from the five countries applied for 130 spots in the Canadian program. Student visas are almost impossible for refugees to get, so this opportunity is one of best options students have to get out Kakuma and continue their education.

But many applications don’t meet the minimum benchmarks or are incomplete. Officials and educators are trying to come up with alternatives, so that students’ only hope for a bright future doesn’t rest on Canada. They’re increasing vocational education opportunities so students can be trained in the food and beverage industry or in tailoring, to enable them to earn a living in the camp.

While waiting for word on her application, Deng teaches classes to primary school girls on sexual assault prevention through Ujamar Africa. She works on an online diploma course through Regis University, one of 10 schools that the camp has partnered with to offer higher education. She also waits to hear about two other scholarships at universities in Kenya.

Deng tries to keep her expectations about the Canadian scholarship low to avoid the devastation she felt when rejected the previous two times. She’s even thought about going to South Sudan despite the dangers there.

Then, in September, after weeks of waiting, the news finally arrives: Deng gets a text on her phone telling her she’s secured a scholarship to Canada. She’s one of 31 applicants from Kakuma, and 124 refugees overall, a majority of whom are girls, selected to begin classes in 2019.

Deng is so happy, she cries for the first 20 minutes after reading the news.

“I knew that I could do this,” she says. “That I deserved it.”

This story about refugee education was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.