Tré never stopped praying. Even when the virus ravaged his sweet mother’s lungs in a matter of days this summer. Or when her casket was lowered into the soil three weeks after her 50th birthday. He never lost what Cindy Dawkins taught her four babies to hold tightest to: the belief that all things work together for good.

On the last Sunday in October, Tré bows his head once more, sitting at the front of West Pines Baptist Church. As the choir sings songs of hope and heaven and God, Tré rocks left and right, his hands clasped, nodding to lyric after melodic lyric. He stands tall, looking fly in his black hoodie, pressed khakis, white Reebok classics, and crisp low-top fade. At 20, Tré is now the man of the house. He’s always been, as the only boy, but now, he feels a heavier load. “As [the coffin] was going down, in my mind I’m like, This is real now,” he says. “I gotta do what it takes. I looked at my sisters, and I was like, ‘That’s my responsibility now.’”

His three sisters don’t do the whole church thing as religiously as he does. Jenny, 24, is the eldest. Zoe and Sierra are 15 and 12, respectively. When their mom died of Covid pneumonia, they joined more than 140,000 children in the nation who lost a primary or secondary caregiver to Covid between April 2020 and June 2021. Children of color have been the most impacted by this compounded trauma of the pandemic: a study co-led by Harvard professor of pediatrics Charles Nelson found that about one in four children who’ve lost a primary caregiver are Black—like the four Dawkins left behind.

Nelson and his 15 coauthors of the Global Reference Group on Children Affected by COVID-19, were the first to call attention to this new group, and coined the term Covid orphans. Similar to when children became orphaned during the AIDS epidemic, the title is born out of the need to classify those dependents who lost one or both parents and suddenly find themselves without someone to provide the basics children need to thrive daily: security, food, shelter, and love. Florida, where Tré and his sisters have lived since they permanently migrated from the Bahamas in 2007, has nearly 8,000 children who have lost a primary caregiver to Covid—the third-highest number nationally, behind California and Texas.

That number is now rising at a faster rate, Nelson says, while local and federal governments remain largely mum on the issue. “Most of us, since March of 2020, have been obsessed with people getting sick and people dying,” he says, “but the hidden cost of the pandemic that no one was really thinking about is the sheer number of kids who have lost parents or grandparents or primary caregivers.”

At one point Dawkins worked two jobs and lived paycheck to paycheck, and the family had bouts of being unhoused, but she always made the small things seem simple. Now, those small things have become daunting for her surviving children, from creating grocery lists and buying the right kind of milk to perfecting the morning routine and making dinners everyone enjoys. Then there’s the matter of missed school assignments and keeping a roof over their heads. The federal government has flooded schools and communities with Covid emergency aid, but no one has created a clear road map or stimulus plan for this demographic, now or for a post-pandemic era.

And still, for every estimated four Covid adult deaths today, one child loses a primary caregiver.

“We need someone to take responsibility for this. Someone to step up and say, ‘Oh, my God, there’s more than 100,000 children who are now left without parents or grandparents to take care of them.’”

Charles Nelson, Harvard University

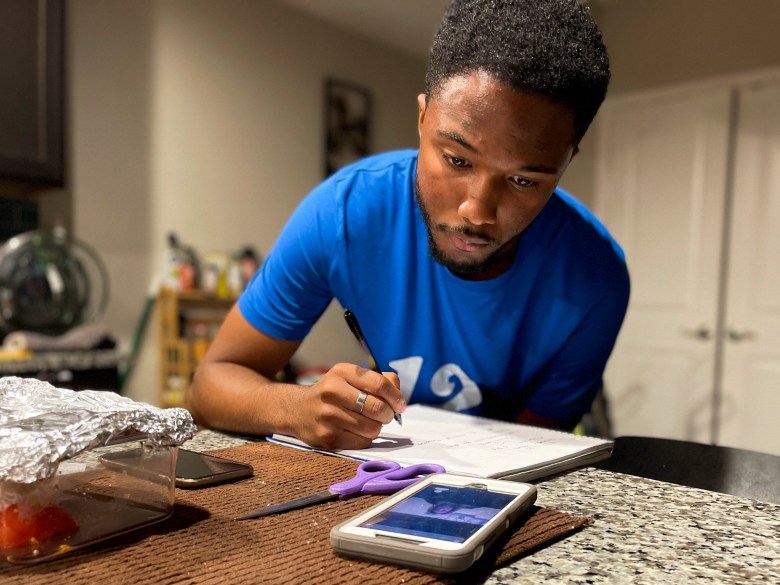

While kids his age stress over dating apps or where to go for spring break, Tré sits at their marble kitchen island divvying up light bills, car notes, and grocery and gas expenses. Since their mother’s death, it’s been a whirlwind of checklists in a rinse-and-repeat survival cycle. An informal network including friends, neighbors, church members, school staff, and some strangers have stepped up to help however they can.

This first week in November is no different: figuring out school drop-offs and pickups, adjusting to new jobs for the two eldest, getting permanent custody of the two youngest, figuring out how to get Social Security survivors benefits, filing for FEMA’s Covid funeral assistance, and worrying about the Cigna bill for their mom’s hospital care in those final days. The siblings keep moving, mourning, one breath at a time, together.

“It hurts, like a physical pain in your chest,” Tré says. “This feels so wrong; it just doesn’t feel like it should happen. Like, why, God, why does it have to be this way?”

DAY 86

Monday, 6:02 a.m. Tré is up after snoozing his 5:30 alarm. Today is his day to drop the girls at school: Somerset Canyons Academy. So are Wednesdays and Fridays.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, he’s off to 7:30 Bible study before work at 9. On those days, Jenny drops off. She always does pickup except when Zoe stays late because of her growing list of after-school-sports commitments. Then, Tré steps in.

“Zoe, Sierra, get up,” Tré says softly before going to the bathroom to brush his teeth. It’s 6:09. To make it to the girls’ charter school by 7:20, they need to be out the door by 7. Latest.

By 6:13, still no action from the girls’ corner room. “Come on, wake up.” Tré walks into their room four more times before they budge.

Zoe and Sierra finally get up and drag their feet. To the living room. The laundry. The kitchen. Fussy. They wipe crusties from their eyes in line for the bathroom.

In these hurried moments, there’s just surviving. There’s just getting through the mundane of everyday life.

“Tré, I figured out why the dryer was making so much noise,” Zoe says, standing in front of his bedroom. It’s almost 6:40. “I forgot to take my ruler out my backpack,” she draws the purple ruler, giggling.

Sierra walks past Zoe into the bathroom with the determined swagger of cranky adolescence. “She’s in a mood,” Zoe tells Tré.

Seven minutes go by.

Sierra puts on mascara, Zoe slabs peanut butter on sliced white bread. The girls, in their khaki bottoms and blue tops, lace up.

They march out the door. 6:59.

Dawkins, who was unvaccinated, started feeling sick in late July, just as the delta variant hit Florida, when the state had one of the highest rates of Covid infections in the nation. Though Dawkins made sure her children washed their hands, wore masks, and social-distanced, Tré says she was skeptical of the vaccine and its potential side effects: “She saw it as, we don’t know a whole lot.”

Exactly where Dawkins caught the virus remains unknown to her children, who recall that she struggled up and down the stairs for days. Her breathing was slower, her movements heavier. Her children sensed something was off, but Dawkins insisted she was fine. She was more worried about the rent. As a birthday gift to their mom, Jenny and Tré promised they’d chip in toward the $2,300 expense. They also pooled their money to get her a nice bottle of white from Publix. The Josh kind.

To celebrate the birthday milestone, Auntie Dedrie, Dawkins’s older sister from the Bahamas, had rented a 12-bedroom Airbnb in Orlando. Dawkins always loved checking out houses. One of her American dreams was to have a home of her own one day. So this was a real treat.

They arrived in Orlando the last Friday in July. Other family members from the Island joined in on the festivities. Dawkins moved even slower, but the family blamed a cold.

On Sunday, her birthday, she stayed in bed most of the day.

“When she finally came out of her room, she was talking about, ‘Food just tastes weird. I can’t even really taste it,’” Tré says. He and Jenny worried it was Covid. But, he says, “Family members were laughing like, ‘Okay, Tré, relax!’”

At Universal’s Islands of Adventure on Monday, as kids dashed around in excitement, Dawkins could barely take a step without getting short of breath, so they got her a wheelchair.

Dawkins spent the entire next day in bed. As the day went on, she became listless. But she refused to go to the hospital. She just needed to rest, she said. The family returned home to Boynton Beach Tuesday night. Dawkins immediately quarantined in her bedroom.

On Wednesday, Dawkins agreed to go to the hospital, but not until after a meeting Thursday afternoon. She had an appointment with Mercer Law, P.A., a local law firm, to complete her USCIS application to finally become an American citizen. She’d toiled almost 20 years and saved $5,000 for the legal expenses. She wasn’t going to miss it.

But when she attempted to go downstairs from their third-floor apartment, she couldn’t make it. That evening, she was admitted to JFK Medical Center. The Covid unit didn’t allow visitors, so Dawkins updated her family by text and video chat. Early Saturday, August 7, Jenny received a call asking if they could put her mom on life support. By 5 a.m., she was dead.

There were no goodbyes. No hugs or kisses or final whiffs. Just a doctor meeting them in the waiting room as the day broke with a monosyllabic script.

We did all we could.

It was too late.

She died.

Sunk into a downy sectional in their rust-themed living room, Jenny remembers the last time with her mom, shortly before calling the ambulance. “I went in the room, and I put socks on her feet,” Jenny says. “I didn’t want to look at her, something felt weird. I asked her if she was okay and she couldn’t talk,” she says, crying. “My mom had no preexisting conditions, nothing. I’d never seen her even get a cold, so I’m like, what happened?”

Tré’s last moment with his mom, simple and ordinary, is one he treasures. His mask on, he danced into her bedroom Wednesday night, “pew-pew-ing” his index fingers as he delivered her vitamins. Dawkins mustered a chuckle. “She was sitting there, obviously struggling to breathe,” he says, “and then she looked at me like, ‘Really?’”

DAY 87

Tuesday, 6:43 p.m. Sierra naps. She usually does after school. Zoe lies on the living room’s brown area rug doing math homework.

Later, Jenny spreads out on the sofa next to Zoe. “We have to check your grades today, right?” Jenny asks.

“I have to do something for English class that I missed before you check,” Zoe whispers.

“What do you have to do? So, what’s your grade in English class now?”

“I think a D?” But the thing is, because, I did it, but I didn’t get a grade on it,” she says in another blushed whisper.

“How did you not get a grade on something that you did?”

“Because she already put in the grade?” Zoe says.

Jenny purses her lips, “What was the assignment?”

“We’re doing—I forgot—it’s hard to explain because we do a lot of things in English.” Zoe runs to her room, grabs a notebook, rushes back into the living room and sinks back down next to Jenny. “Like this: how to write paragraphs and stuff. And simple, basic things like, you know, how you have like they, them, they’re, and their and all that stuff? And there’s wrong ways to do it and how to spell it? Like you can’t put got in a sentence or gotta and stuff like that?”

Jenny looks at the notebook, tells Zoe to do it over, to take her time, and reminds her of the monthly $25 she and Tré give the girls for A’s and B’s.

“I knooooow,” Zoe shrieks. She’s been eyeing the iPhone XS Max—the same one Sierra got last Christmas from their mom when her report card was looking right.

One of the first calls Jenny and Tré made that Saturday morning was to Janie Yoshida. Miss Janie, as they affectionately call her, has known the family since the fall of 2018, when she first learned they were living in motels and hotels. One evening when picking up her daughter from school, she spotted Tré walking to the bus stop; he was the lead in the same school play as her ninth grader. She gave him a ride to a local motel and began dropping him off regularly. She helped the family as subtly as possible. She’d pull into a Burger King and say, “Oh, I don’t feel like cooking tonight, let’s just grab a burger,” and get Tré and his sisters some food too. “Oh, it’s buy one get one for a penny today?” She’d get even more.

When Yoshida finally met Dawkins, she learned about how one fallen domino had disrupted the rest of her and her babies’ lives.

Dawkins had been a longtime server at the Ritz, but lost her job in 2018. Without that next check, the family was later evicted. She eventually got a job at Souvlaki Fast, a Greek restaurant, and a second one working at Jax Bistro and Bar. But rebuilding check by check meant some days she had to choose between the motel bill and gas for her car. At times, Tré remembers she could only afford $5 for gas: just enough to get herself to work but not her kids to school, which they occasionally missed. On some of those days, Tré says Dawkins dropped them off at the Best Buy close to their motel. They’d spend the day at the store, and she’d pick them up after work.

Tré, a senior at the time, remained quiet about his family’s situation. He feared if a teacher or administrator found out, they’d report his mom to the Department of Children and Families and take them away. Tré says they were unhoused from 2018 through the beginning of 2020, moving from motel to hotel. With an eviction on Dawkins’s record, she couldn’t find anyone who would rent to her.

Dawkins never wanted her children to see her complain. She only cried in the shower, she once told Yoshida after the two grew close. Eventually, Yoshida rented an apartment in her own name so Dawkins didn’t have to note her prior eviction. Dawkins assured Yoshida she would never miss a rent payment. And she never did.

“When I took her the keys that morning, I asked her, Do you need help moving?” Yoshida remembers.

“No, no, I have a friend coming,” Dawkins insisted.

“It was literally three bins,” Yoshida says. “That was all their belongings.”

The first thing Dawkins did in their new apartment was cook rice and peas, mac ’n’ cheese, and fish. “She tells me, ‘I haven’t been able to cook dinner for my kids for three years,’” Yoshida remembers. “‘I just want to make dinner for my kids where we sit down and eat.’”

When Tré and Jenny talked to her the Saturday their mother died, Yoshida wept. “She was doing great,” Yoshida says, still in shock. “The kids were doing great.”

Now they were in a panic that they’d be reported to DCF or relatives from the Bahamas would take their baby sisters away. Yoshida eased the children’s minds and promised to cover the rent through the end of the lease in February and set up a GoFundMe. Tré says that the law firm helping Dawkins with her citizenship papers refunded $1,760 of the $5,000 fee and the women’s group from Yoshida’s church raised more than $3,000, mostly in gift cards.

Stephanie Horsely, a teacher at Somerset, worked with the school’s assistant principal and other staff to provide Zoe and Sierra with uniforms and waive their activities fees, and she arranged for HelloFresh groceries to hold them over as they figured things out.

To help Jenny and Tré navigate the barrage of legal matters, like getting custodial guardianship of Zoe and Sierra, Yoshida connected them with Jewish Adoption and Family Care Options (JAFCO), a social service and residential program for children and families in Sunrise, Florida. JAFCO led Jenny through the process of getting a court-appointed guardianship, which would make her eligible for financial-assistance programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

The agency also advised Jenny not to forget the little things: getting the girls their yearly physical. Being mindful of her self-care, sleeping, eating, drinking water. Because in the doing and going and doing some more, it’s easy to become neglectful, especially as a young adult thrust into parenthood. Jenny and Tré now wondered, what would happen to their sisters if anything happened to them? Dawkins left no will or life insurance, and her children continue to scramble check to check.

Jenny works at a private pediatric dental practice as a dental assistant. She started in August after finishing an externship as part of a 10-month dental program. Before their mom died, she planned to move up from dental assistant to hygienist, which would allow her to set her own hours and pay, a goal her mom encouraged. Her plans have to wait now, possibly until Zoe and Sierra get settled and are off to college.

Tré is a customer-service representative at AeroCare, a medical-equipment company. He started in July. But now, he wants to be a firefighter, and is chipping away at the goal bit by bit. To do that, he’ll have to go back to school. The first step is an EMT program at Palm Beach State College that costs $2,300. His neighbor, Raj Kamthe, offered to cover the bill. “Without education, we have nothing,” Kamthe says. “That helps bring out a lot of people that could possibly go into poverty.”

All sorts of people have stepped in to help Jenny and Tré navigate their new world of bills and expenses. A friend who owns a small business showed Tré how to make budgets and lists. Jenny now sets aside about $500 for bills from her paychecks. They opened a savings account for Dawkins’s Social Security survivors benefits, which go to Zoe and Sierra as dependents under 18. They figured out they need around $200 every two weeks for groceries. The list is the same: two loaves of sliced bread, two gallons of milk, eggs, a 40-pack of bottled water, lunch meat, cereal, noodles, big bags of individualized chips, cranberry juice, ground beef, chicken, pork chops and white rice.

Jenny’s go-to dinner for the crew is white rice with baked chicken or pork chops. She’s still working on perfecting their mom’s signature dish. “I’m not touching peas and rice until I know for sure, for sure that I got it,” Jenny says. On lazy nights, it’s homemade burgers.

Huge expenses still loom. There’s the matter of the burial cost: the funeral home and casket fees were over $5,300. The headstone cost about $2,400. They are eligible to receive FEMA’s Covid-19 funeral assistance, once they manage to submit an application.

Then there’s an outstanding balance from the health insurance company. The statement was addressed to Dawkins for her final days at JFK Medical Center.

What My Cigna Plan Paid: $0.00

What I Owe: $42,751.82

“Who’s supposed to pay that?” Jenny says. In her frustration, she has just let the statements pile up.

Miata Ezueh, a targeted-case-manager supervisor at a private social service agency who helped raise money for Dawkins’s children, says caseloads have “increased exponentially.” She adds that “if Tré and Jenny were just a few years younger, they would all be in foster care and maybe spread out. There’s no guarantee they would’ve kept them together.” She says she plans to help Tré and his sisters for the long haul, to help provide some security and guidance.

“My mom would’ve hated for us to be separated even more than us being homeless together,” Tré says. In those early days following Dawkins’s death, scrambling to make sense of it all, Tré says he and Jenny agreed that “we’re just gonna struggle through it. We’re going to do what we gotta do. If that means we gotta stay on somebody’s couch. We gotta stay in the car and not tell anybody about it. We’ll do what we gotta do.”

DAY 88

Wednesday, 6:27 p.m. It’s burger night. Jenny mashes ground beef, fires up the mini grill, and places buttered bread in the oven.

At the kitchen island, Tré readies for a Zoom orientation on his phone for the EMT training program.

Zoe describes a love triangle she finds herself in. It’s as complicated as ninth-grader affairs can get. There was a boy, a school dance, and then, another boy. But thank God for Sanai, her best friend who’s been there through it all. Sanai was her first call when she found out her mom had died.

Sierra strolls into the kitchen at 6:38, both hands buried under her blue T-shirt. Everyone stares at her. “What?” she says in revolt to the room.

Tré shifts between taking notes, nodding at his cell phone screen and gently poking Sierra to cheer her up. She fights him off, rolling her eyes and sneaking smiles.

Sierra says her seventh-grade math teacher gave her an F on last night’s homework. “She said I didn’t do it,” Sierra says. “Did you?” Jenny asks. “It was online,” Sierra says with a hiss.

“Does she know you don’t have a laptop?” Jenny asks. “Did you tell her?” Tre says in the same breath, lifting his head from his iPhone. “You couldn’t do it on your phone?” Zoe interjects.

Sierra rolls her eyes and tugs at her T-shirt, “No.” Another hiss.

“So your teacher thought you had a laptop, or—” Tré asks. “Yes, cause I did it last week with Jo’s laptop,” Sierra says with a long huff.

7:19: They cut onions and tomatoes, dress their burgers on white sliced bread, and squirt ketchup and mustard. Jenny says a rushed prayer before her first bite. Those little somethings their mommy had taught them to do, they were doing.

When classes started at Somerset three days after Dawkins died, Zoe and Sierra missed a combined nine days of school.

“I didn’t feel like it was right for me to go to school yet,” Zoe says. “I didn’t feel ready to.”

Now, getting an A in biology or placement in advanced math feels meaningless, replaced with thoughts of the right words to say to well-wishing friends and remedies for running images from the funeral of a stuffed version of what was once their mother. Without her “good job, baby,” who are they striving for? Already, this school year—their first in person, full time, since spring 2020—was not going to be ordinary.

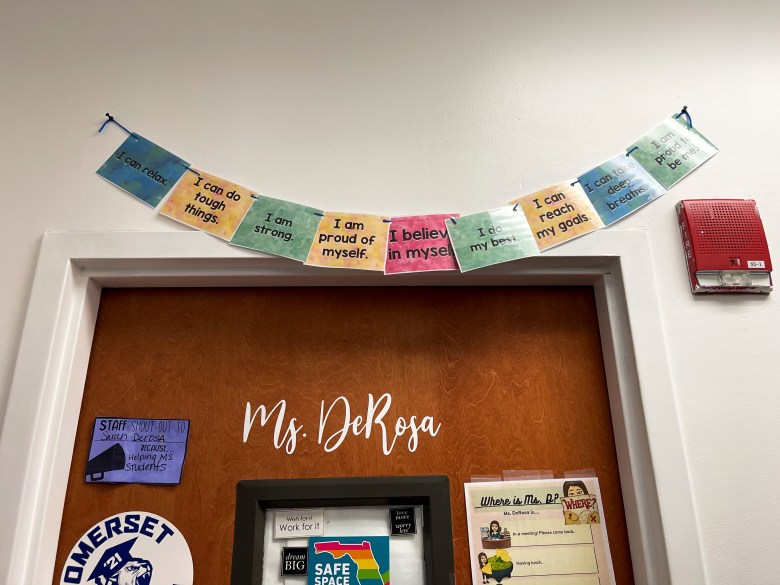

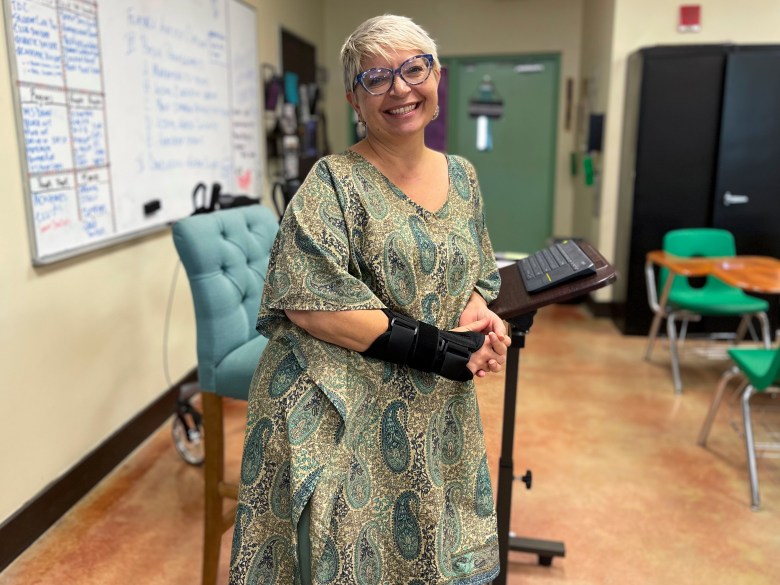

The school’s assistant principal, Ashley Tokan, says despite the missed days, the girls’ academic performance appears to be progressing well from what she hears from Zoe’s counselor, Kayla Slocum, and Sierra’s counselor, Sarah DeRosa. Both women are in touch with the girls’ teachers and focus on building rapport and trust.

“Being in the school setting, if the student is doing okay, you don’t necessarily want to bring up all those emotions,” Slocum, the school counselor for eighth and ninth graders, says. “I don’t want to make [Zoe] talk about things at school to get her upset during fourth period and she has to go back to class crying.” DeRosa, who works with sixth and seventh graders, says she takes a solution-focused approach with Sierra, who she’s noticed gets more teary-eyed or cries when talking about things that upset her at school. “If there’s something that we can fix here at school in the moment, I think about ways to fix that,” she says. For example, “when she has conflicts with her friends, we’ve been talking about taking ownership of our feelings and our actions, because we can only control our actions.”

DeRosa says the counselors plan to start small student groups to help students like Zoe and Sierra who’ve experienced layered trauma because of the pandemic. In the last school year, there were three counselors for all middle and high schoolers. This year, with roughly 1,750 students, the school added one more.

Being back in school helps Zoe and Sierra mourn the loss of their mom: in the simple act of getting dressed in the morning, the anticipation of hanging out, talking about a funny meme or viral video, walking past a crush, complaining about how hard that assignment was.

“It’s been fine for me,” Sierra says. “It helps keep me busy and keeps my mind off of it.”

The girls also think about how their mother would want them to carry on. She was strict on them to do well in school, making sure they made themselves proud above all else. “Mom just raised us to be like, to handle situations maturely,” Zoe says. “That’s why we’re not like all hectic and stuff. I get how people feel like how we should be. But I’m thankful that she raised us to be okay.”

“Yeah, because like she always used to say like, when we talk about religion and God, she said, um, I know I’m going to heaven and all that stuff,” Sierra says. “Yeah, so this is the way that I like cope. Like knowing that she’s in heaven.”

Zoe joined volleyball and practices or assists coaches in other sports like soccer. Sierra desperately wanted to do cheerleading but didn’t make the squad. She may try out for the All-Star competitive state team in the spring, or soccer next year. Maybe.

Their mom played softball, soccer, and volleyball and ran track when she was younger. This year, Zoe joined the volleyball team. Tryouts were before the birthday trip to Orlando. “I was happy I got to tell her I made the volleyball team before she passed,” Zoe says. After games and practices, Zoe sometimes talks to her mom. She looks up to the sky and asks, “I did good, right?” her full cheeks rising at the thought of her mom pumping fists at her spikes.

A month after her mom’s death, Zoe’s volleyball coach, Morgan Valinoti, says Zoe broke down sobbing in the locker room after an especially tough practice. School medics got involved and identified the outburst as a panic attack. “It made her finally feel her feelings, which she hadn’t dealt with before,” says Valinoti. Tré left work early that day to be with his baby sister. They hugged and talked it out.

“Sometimes it can be overwhelming,” Zoe says. “I have my moments since there’s so many people surrounding me. It’s hard to explain. I don’t like crying in front of people, so I usually just keep it in until I get home.” On those days when she needs to escape the attention and prying questions, she finds Horsely, Somerset’s journalism teacher, who initially coordinated with the school to get the girls uniforms. “If I don’t feel like talking to my friends at lunch, I could just go to her classroom.”

Horsely is the school mom. Students visit her classroom for advice on friendship drama and college applications or to ask for a maxi pad.

Horsely knows at least nine students who told her in confidence they’ve lost a parent or grandparent to Covid last year. She believes the school didn’t always know. “Do I think our school has a foolproof plan? Absolutely not. They’re overwhelmed,” Horsely says. But, “it’s no longer an excuse to say, ‘We don’t know.’”

Tokan says the school rallies to provide help to kids beyond academics and counseling once they hear about it, “because they’re our students, they’re like our kids.”

“Last year, we had a kid that was homeless and the senior counselor reached out to staff,” she says. “We were able to find a place [and] donate things like lamps, bedsheets, and got him a fridge. All that stuff to get him set up.”

We tend not to put children first in this country, says Nelson, the Harvard professor of pediatrics and co-author of the research on Covid orphans; he also studies the effects of adversity on brain and behavioral development at Boston Children’s Hospital. “Schools play an important role in monitoring children’s physical and mental health. The question is, are they getting guidance about doing that?” he says. “[Can] they recognize depression or anxiety or something even more serious in a child?”

DAY 89

Thursday, 6:44 p.m. It’s game night. Tonight is Air Pictionary, and Zoe and Tré go against Sierra and Jenny. “A clue can be drawn in any order, the easier clues appear first,” Zoe meticulously reads the instructions.

“Okay,” Tre says.

“The first four clues are worth one point,” Zoe continues, “the last clue is more challenging and worth two points. It’s marked with a plus two stars.”

They stare at her. Mm-hmm. “The clues card are double sided and –”

“Oh, Zoe, stop talking, let’s go,” Tre says. “We understand already. Okay? You’re going first.”

One by one, they draw floss, bracelet, horse, skate, flinging their hands and bodies all over the place to demonstrate the use of each thing. Zoe circles the stick wildly, trying to draw gloves. “What isssss that?” Jenny yells.

They laugh harder with each card. Even Sierra, with her preteen-mean-girl swag, does all the moves, laughing the loudest at times.

7:23. After Tré and Zoe win the last of the three rounds, he heads to Bible study at First Baptist Boynton, where the family once attended with their mom. This one thing she was diligent in he carries on.

Governor Ron DeSantis, who recently requested $3.5 million from the state legislature to establish a civilian military force, has boasted of the state’s trending low infection and hospitalization rates. Jason Salemi, an epidemiologist from the University of South Florida who has a database that tracks Florida’s Covid cases and trends, says it’s a problematic outlook. “It’s vitally important that we remember how we got here,” he says. “We’ve experienced record hospitalization rates in every age group, record numbers of deaths, and all of those things have far exceeded any other period of the pandemic.”

Around the time of Dawkins’ death, a fully vaccinated man in North Palm Beach, Vincent Konidare, contracted the virus on August 2 and died on September 19. The 58-year-old white man left behind two children and a widow who remains baffled by his death.

There was also a 33-year-old Black father of four, David Dalloo, who died at the same hospital as Dawkins on August 28. His widow said everyone in the home contracted the virus from one of their asymptomatic children shortly after school resumed.

“It hurts, like a physical pain in your chest,”

Tré, 20, who lost his mother to Covid this summer

Sarah Franco, the chief executive of JAFCO, the agency helping Tré and his sisters since Dawkins’s death, has noticed the increasing numbers of Covid orphans in Florida. She recalls two recent cases where families with children each lost a partner to Covid. JAFCO stepped in “and gave the families respite and tried to take the role of that other parent and provided whatever resources they needed,” she says. In Jenny’s case, JAFCO is helping the family through its privately funded family preservation program. “It was really about prioritizing and breaking down their long-term and short-term goals,” says Shea Pucci, one of the JAFCO clinical supervisors who conducted Jenny’s initial intake. “And, helping them navigate what it’s going to be like to be young parents.”

Florida’s Department of Children and Families did not respond directly when asked if they are tracking children who have lost parents or guardians to Covid. But the number of children in Florida’s foster-care system has increased by 44 percent since the end of January 2020, going from 8,132 to 11,735 through the end of October. A DCF spokesperson said existing resources—like therapy with a licensed mental health professional—can apply to children who have lost a primary caregiver. But no additional resources or programs have been publicly announced for the growing number of Covid orphans in the state.

In May the city of Boynton Beach, where Tré and his sisters still live, received $6,823,952 as part of its allocated $13,647,904 American Rescue Plan Act’s Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds. Last month, the city held a meeting to ask community members and nonprofits how best to use the money. But “Covid orphans is something that has not come up in any of these community conversations,” says David Scott, the city’s director of economic development and strategy.

“My mom would’ve hated for us to be separated even more than us being homeless together,”

Tré, 20

The city’s mayor, Steven Grant, who is running as an Independent to unseat Senator Marco Rubio, admits there’s more to be done. He hasn’t carved out anything specific for Covid orphans. “We do what we can with the rental and utility assistance,” he says. “We’re focusing on the totality of the community. Because trying to draw a fine line of ‘Well, your parents didn’t die, but they were in the hospital for three months with Covid, sorry we’re not going to give you any resources,’ I feel that won’t be right. Even if you didn’t lose your parents, if your parent lost their job and is unable to find a way to support the family and then they’re dealing with mental health issues, it’s still a huge burden.”

Pathways to Prosperity is one of the nonprofits the city of Boynton Beach recently partnered with to dispense $75,000 in American Rescue Plan funds. After speaking with Vanity Fair and The Hechinger Report, Mayor Grant notified the group that Dawkins’s children needed assistance. The organization said it provided the family with two laptops for school and that it will give the family full rental and utility assistance for three months, paid directly to the landlord and utility company. Scaling this kind of intentional aid could help address other children who find themselves without recourse.

Nelson, the Harvard professor, says local governments need to be tracking this growing demographic. “We need someone to take responsibility for this,” he says, “someone to step up and say, ‘Oh, my God, there’s more than 100,000 children who are now left without parents or grandparents to take care of them.’”

DAY 90

Friday, 2:54 p.m. Jenny is off today. She has a check-in call with JAFCO, then stops at the Wawa gas station on her way to Somerset. Before hopping out of the car, she puts on her white mask and snaps on gloves. She adds $20 to the pump.

“Let’s see how much that gave me?” She watches as the lever rises. “Okay.”

At 3:27, she picks up Sierra, who drags her feet to the car. She is in a mood. A teacher took away her jacket that morning.

The girls don’t have jackets with the Somerset emblem because Jenny thought only their uniforms needed to include it. She’s going to speak to someone—another thing on the growing list of to-dos.

“There’s always something now,” she says. “We just tryna live to be honest.”

Jenny doesn’t cry in front of the girls. She cries in the shower or in her mom’s bed, where her scent and reminders linger. No specific memory triggers her; it’s the bare absence.

When she watches old cell phone videos of her mom, she laughs. “She knew how to have a good time,” she says after one. “There are days where I just think about her, and it’s like, Oh, wow.” When she looked at the calendar one month after her mother’s death, on the seventh day, it was like, oh, wow.

Jenny has tried to step into the role of the maternal figure and soften the impact of their mom’s death on Zoe and Sierra’s emotional health, schooling, and self-esteem. “I ask them every now and then, Okay, so how are you feeling, sister to sister, tell me, and they’re, like, ‘Oh, my gosh, can you not?’” Jenny says. “I don’t want them to be traumatized and I don’t know about it. I told them that I want them to do counseling, but they’re like, No, no, no. They’ll say, ‘I’m fine, I cried the other day.’”

“I have my moments since there’s so many people surrounding me. It’s hard to explain. I don’t like crying in front of people, so I usually just keep it in until I get home.”

Zoe, 15

Sitting by their apartment complex’s pool with striped chaise lounges and recliners, Zoe and Sierra are hushed but thoughtful. Zoe breaks one quiet beat with a giggle. She remembers how her mommy used to “like, literally yell to communicate with us in the house. She’d be like, ‘Zoe come here’ or call me in her room to do something for her or get something for her. And I’m like, just text me.”

She points to the sky. “She’s up there having the best time with her mom and her other sister, watching down on us.”

No single moment has been harder to get through than the next for the girls, “but some days when I think about it, it’s like, oh, we’re going to be celebrating Christmas without her,” Zoe says, “Thanksgiving without her, her birthday, Mother’s Day. It’s like I’m not ready for it.”

She forgot her last words to her mom but remembers lying next to her that Wednesday night. “I was still getting over being sick too,” she says, “and I fell asleep for like two minutes and she tapped me and told me, ‘You have to go in your room cause you might get more sick,’ and I went in my room and I went to sleep and that was the last time.”

For Sierra, that last moment with her mom is a cherished one. “I called her when she was in the hospital,” she says softly, her feet pressed against a white patio table, rocking up and down. She pulls at the tips of her braids.

“Did she say anything?” Zoe asks. They’ve never talked about it.

“I asked her some questions,” Sierra says, her scrunched lips twist left, then right. “I don’t really remember what, but she was like nodding her head, she didn’t talk.”

“Because she had her mask on?” Zoe says. A ventilator was over their mother’s nose and mouth.

“Yeah.” Both of Sierra’s index fingers dig into her shoes, her head hangs down. “The last thing I said to her was, I love you. I don’t even, like, say that that much. I had a feeling like deep down inside that she wasn’t gonna make it.”

“When did you call her?” Zoe’s voice rises with tiny cracks.

“The day before she died.”

In the 91 days since her death, Dawkins’s babies carry on best as they can.

Tré starts the cloudy Saturday with breakfast at John G’s Restaurant with friends from church. Zoe talks to Sanai about some boy who did something or other and how helping to manage the soccer team is, like, so dramatic—she does so much. Sierra scrolls through her social feeds and twirls her long box braids—a hairstyle she did herself. Jenny goes out. She might chill at the beach.

Next Saturday, Tré is off to a retreat with the men’s group from West Pines Church—the first time he’s leaving the apartment and his sisters for an extended period since their mom died. “I have not been great at taking a minute to breathe,” he confesses. He looks forward to being by “water so crystal clear at night the moonlight shines directly to the bottom.” Away from the pangs of responsibilities. When those tension-filled moments come, when he and Jenny fight like an old married couple, or when the shadow of grief threatens to drown, Tré taps into the faith that has sustained him, and he remains still.

“He’s freakishly strong,” Jenny admits. “His faith is beyond, like nothing’s gonna break it.” She would never tell him this, she laughs, but “he makes everything better.”

Tré, the sweet brother, renewed a promise the day he saw his mom go into the ground, to always protect and love on his sisters.

Tré, the grieving son, cries in his car, where his sisters can’t see him, when thoughts of his mother’s sacrifices bubble up without warning. He remembers everything, big and small, and cries some more. Then, he prays for peace.

This story about Covid orphans was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, in partnership with Vanity Fair. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

I had tears in my eyes, the strength of this family!