DAVIS, Calif. — Only streetlights cut the darkness as University of California, Davis student Malik Vega-Tatum climbed into his car on a Wednesday morning in January. After arriving at La Tourangelle Community Garden in Woodland 20 minutes later, he got right to work, using a hoe to tend frost-kissed rows.

Since the school year began, Vega-Tatum has given more than 356 hours of his time to Yolo Farm to Fork, a nonprofit that supports school gardens and farm-based education. In exchange, he will receive $700 a month for 10 months from the #CaliforniansForAll College Corps program, class credit and experience with food production science. When he reaches the 450-hour mark, he’ll get a $3,000 award. He’ll graduate with $10,000 less debt and with work experience he hopes will give him an edge when he applies to medical school next year.

Vega-Tatum has held jobs before, but College Corps is different. Conceived as a domestic Peace Corps or “California GI Bill,” it is designed to help students pay for college while facilitating community service throughout California to help the state tackle some of its most pressing challenges. Some 3,200 students, many of them the first in their families to attend college, are participating in the inaugural year of the New Deal-esque program, in service jobs in K-12 education, food insecurity and climate mitigation.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, whose administration launched the program, has called it a way “to restore the social contract between government and its citizens,” one “that says if you work hard and dedicate yourself in service to others, you will be rewarded with opportunity.” The participants, who attend 46 educational institutions from College of the Siskiyous near the Oregon border to the University of San Diego, need opportunity.

Sixty-eight percent of College Corps fellows are low income, in a state where the average student loan debt is roughly $37,000. More than 15 percent have lived in California for years, but lack the immigration documentation necessary to qualify for most financial aid. The creators of the program hope other states will replicate it. Yet critics and academics have raised concerns about its high price tag and administrative overhead, and the fellows’ experiences make it clear that the program is no panacea.

Related: Debt without degree: The human cost of college debt that becomes ‘purgatory’

Up to 70 percent of undergraduate students work, but jobs have historically been seen as an academic hazard. “As you increase the number of hours you work, it crowds out opportunities for a host of things, from sleeping to studying,” said Anthony Abraham Jack, an assistant professor of education at Harvard University and author of “The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges Are Failing Disadvantaged Students.”

Yet working during college is also associated with increased earnings afterward. These findings hold across many controls, including socioeconomic status and work experience before college, suggesting that the relationship is causal. Working in college signals to employers “that this person has soft skills, that they can get there, that they can take direction, that they can collaborate as part of a team,” said Daniel Douglas, a researcher and lecturer at Trinity College who has studied the issue.

When work aligns with a student’s course of study, college jobs can also impart hard skills and build social networks. Low-income students are less likely to have those networks through family and acquaintances or be able to build them through unpaid internships. Jobs bring recommenders into the lives of students, which is especially important for transfer students like Vega-Tatum who don’t have as many years on campus to form bonds.

The 24-year-old now runs hurdles for the UC Davis track team while pursuing a double major in psychology and African American studies, and obstacles peppered his path off the track as well. Vega-Tatum grew up in Stockton, a community mostly known for its high crime rate, and played three sports in high school. “The plan was to get offers” from four-year colleges, he said, “and everything be paid for.” That didn’t happen. So he enrolled in community college before starting at UC Davis in the fall of 2020.

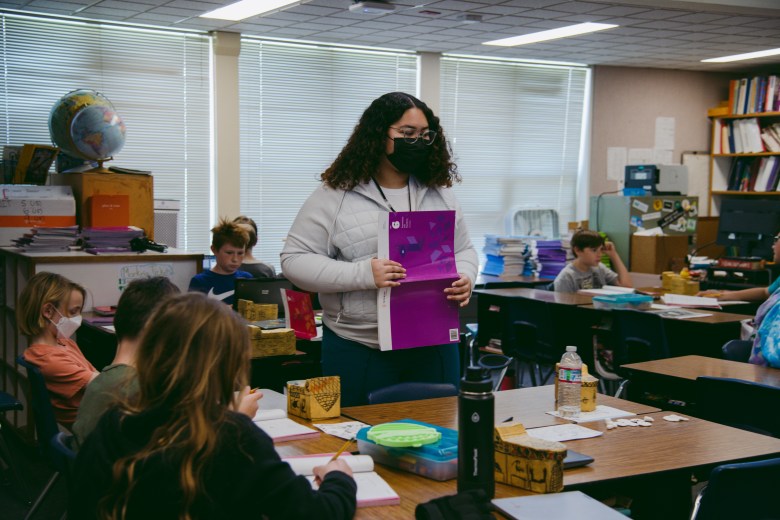

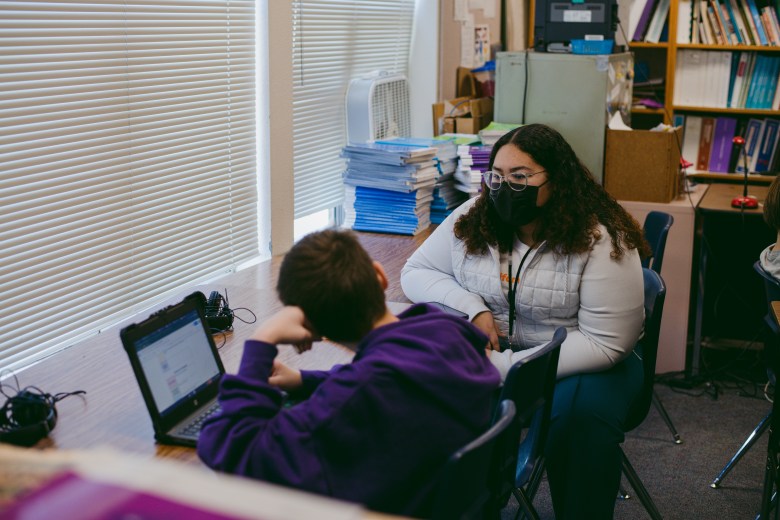

While Vega-Tatum nurtured seedlings on that Wednesday in January, UC Davis junior Markeia Warren, 19, arrived for her College Corps job as a teacher’s aide for a sixth-grade classroom at Patwin Elementary School in Davis.

The school looks different than hers did back in Inglewood, California, and not just because there are so many white faces, while Warren is one of the more than 80 percent of College Corps fellows considered a person of color. She wasn’t reading at age level in kindergarten, she said, so for first grade, she was placed in a Special Day Class, a setting that’s intended for students with severe disabilities. She languished there until seventh grade, reading “baby books like ‘Cat in the Hat,’” she recalled.

Her grandfather, who worked in a cookie factory, and her mother, who was a caregiver for the elderly, didn’t know enough about the education system to question it. Even after Warren excelled in high school and was told she should apply to college, she thought, “I don’t think I’m what college is supposed to look like … and I don’t think I can pay for it.”

But she made it work with financial aid plus 30 hours of work a week at a gas station. “It was pretty stressful,” she said, “I’d be like, ‘Oh my gosh, I don’t have time to do this assignment.’”

Warren learned about College Corps from an email targeting first-generation students and thought, “I’m not going to waste my time.” But then, she said, “I saw that big dollar sign and was like, ‘You know what? Let me pull up.’” Now she’s been able to spend time at Patwin and on classes instead of the gas station. Looking back on elementary school, “it seemed like no one cared,” Warren said, “So that’s why I want to work in education, because I know there may be students who feel like that.”

She laughed as she added, “Markeia Warren shall fix the system.”

Related: Unpaid college fees keep thousands of students from graduating

In a sense, she’s already helping to do that. Staffing issues plagued many school districts before the pandemic, and then got more dire. At Patwin, Principal Ben Kingsbury said he’s had to cover for absent teachers and aides and cope with a big drop in volunteer support from parents. “Everything gets stretched thinner and thinner,” he said, until there’s a point where “if we lose one more person, things stop working.”

College Corps fellows provide “extra eyes and ears, and it just makes the whole system less fragile,” said Kingsbury. While schools and community organizations often struggle with episodic volunteerism, the yearlong commitment — perhaps more, if the fellows apply for a second year — means “you can build capacity and students can get something out of that,” he said.

Of course, long-term volunteers have been placed at schools through the federal AmeriCorps program for decades. But those grants can be hard to manage for smaller school districts and the nonprofits the College Corps program targets, said Stacey Muse, who was the executive director of Nevada Volunteers before being hired by UC Davis in part to assist with College Corps.

College Corps addresses other shortcomings of federal programs. Federal Work-Study, which reaches 600,000 students each year with a budget of roughly $1 billion, typically offers students $2,340 to work part time on campus, which isn’t enough to cover their expenses. Yet, if they work additional jobs, they can lose their eligibility for federal financial aid. And research has found that the program disproportionately benefits students at more expensive institutions.

In contrast, under a pandemic-era waiver from the U.S. Department of Education, the $10,000 that students receive via College Corps doesn’t count against their federal financial aid eligibility. There’s no guarantee, though, that the waiver will be extended.

College Corps also benefits students like Elena Orozco, 36, who are excluded from federal financial aid and Federal Work-Study. “I am undocumented, so my family, the help that’s available, it’s not very much,” said Orozco, a student at Sacramento City College who moved to California from Mexico with her mother when she was 4.

Before College Corps, she juggled classes while supporting her young son by working in restaurants, sometimes two shifts a day, never knowing how much money she’d bring in or when she’d be free to reclaim the sleeping boy from relatives. Each time he got sick, she worried about getting fired. Now that she’s a fellow, working at an organization that supports primarily non-English-speaking families, she can pick her 9-year-old up from his after-school program and spend the evening with him.

But not all student parents can participate in College Corps, because of its requirement of a full-time course load. And working out in the community, rather than on campus, has downsides. “The more time you spend away from campus, the smaller the window for you to access institutional resources” like “career services, mental health services,” said Jack, the Harvard professor.

As an undergrad at Amherst, Jack had the opportunity to see four-star generals, doctors, poets, activists and more. Missing out on those events doesn’t just come at a cultural and educational price; it also affects something else research shows is essential to collegiate success: belonging.

“Eighty percent of college happens outside of class time,” Jack said. “When you see your peers are able to go to any and every event that you can’t,” he added, “it can eat at a student’s sense of belonging.”

The College Corps program costs about $155 million a year, more than $146 million of which is paid by the state.

Markeia Warren said she doesn’t have time to attend events of the sort Jack described, since she works for Target and California Youth Connection, an organization focused on transforming foster care, on top of her hours at Patwin. But the College Corps work feels meaningful: “It doesn’t feel like I’m working,” she said. “It feels like I’m having fun.”

She does, however, go to EDU 198, Davis’ mandatory College Corps class. Sessions cover job training topics like understanding nonprofit organization structures and what to watch out for in a Craigslist job posting (for example, cash-only, a too-good-to-be-true wage, typos, text shorthand like “pls,” and the offer to work from home).

Vega-Tatum said the class has helped him build a bit of a community on campus. “It’s not like, ‘Oh, we’re just classmates,’” he said. “It’s more like, ‘We’re in this together.’”

Related: ‘Revolutionary’ housing: How colleges aim to support formerly incarcerated students

The College Corps program costs about $155 million a year, more than $146 million of which is paid by the state. The rest comes from federal AmeriCorps money. More than half the program’s budget goes to College Corps’ administrative overhead, which includes the salaries of student advisers (each of whom works with about 40 fellows, far lower than the typical caseload), and those who manage relationships with the program’s 600 partner organizations.

Critics have said that administrative share is too high, but Josh Fryday disagrees. “Service programs don’t work if you just throw people out there and say, ‘Go serve,’” said Fryday, a former Navy officer who is California’s chief service officer, a cabinet-level position created under the Newsom administration. “It’s not like your defense budget is just hiring a bunch of soldiers to just go out there and do it. You have to have an entire infrastructure and support system to actually allow them to do their job.”

Fryday said he and Newsom were inspired by the concept of service embraced by Sargent Shriver and Robert F. Kennedy, and also by research on the power of volunteering to stave off anxiety and depression and underemployment statistics (41 percent of college graduates ages 22 to 27 are underemployed, meaning they are working in jobs that typically do not require a college degree).

“Let’s deal with, one, the student debt crisis, but let’s also deal head-on with the crisis of our democracy where people feel very isolated from each other,” Fryday recalled. The state has since launched several volunteerism programs that double as workforce development, including ones open to youth not on the college track.

“As you increase the number of hours you work, it crowds out opportunities for a host of things, from sleeping to studying.” Anthony Abraham Jack, an assistant professor of education at Harvard University

Anthony Abraham Jack, an assistant professor of education at Harvard University

“We believe strongly the federal government should be doing this, and every state should be doing this,” said Fryday. He said the state has contracted with the education research group WestEd to complete a two-year evaluation of the program’s impact on college completion and other measures.

For an individual, especially at a community college, participating could mean “the difference between them graduating or being able to successfully transfer to a four-year institution or not,” Jack said. “California is a model” in that sense, but “this is not a cure-all” for low-income students, he said.

Indeed, Vega-Tatum describes a mixed bag. On the one hand, the program offers him the flexible scheduling that research shows is more conducive to academic success. He can shape his work hours around exams and ice baths after track practice. And food production and nutrition tie into Vega-Tatum’s intellectual interests and his desire to give back to communities like his, which have a lot more going on than just gun violence, he said. That makes his hours in the garden a far cry from the ones he spent hiding in the bathroom of a warehouse he was working in at the time, thinking, “What am I even doing here?”

At the same time, he said, “Work is work.” After heading home to grab a shower and a handful of snacks that Wednesday, Vega-Tatum got in a workout, went to a biology professor’s office hours, prepared a study guide, went to a class, and, at 7 p.m., sat for an exam. Afterward, he drove home, ate dinner, did homework, and made a to-do list for the next day. At 11:40, he turned off his light, his alarm set for 5 a.m. so he could make it back to the garden by daybreak.

Warren sleeps even less. But the monthly disbursement from College Corps pays for almost two-thirds of her rent. The way she sees it, “You’re literally getting paid to pursue your dreams.” She added: “I started pursuing my passion at 19. I don’t know people that can say that, especially from where I grew up.”

This story about College Corps was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.