CLEVELAND — Eric Gordon, CEO of the Cleveland Metropolitan School District, is on an extended farewell tour full of surprises. It’s a chilly Wednesday in April at the end of his last-ever quarterly meeting with the district’s parent advisory committee. The group, made up of people with kids in the school system, functions as a communications channel between other parents and school principals and teachers.

“You all know that I call your kids my kids, and they won’t stop being my kids,” Gordon says, wrapping up the meeting. “Just because I stop being CEO doesn’t mean they stop being my kids. Thank you for letting me be a small part of your families and your lives.” He takes off his glasses, wipes his eyes.

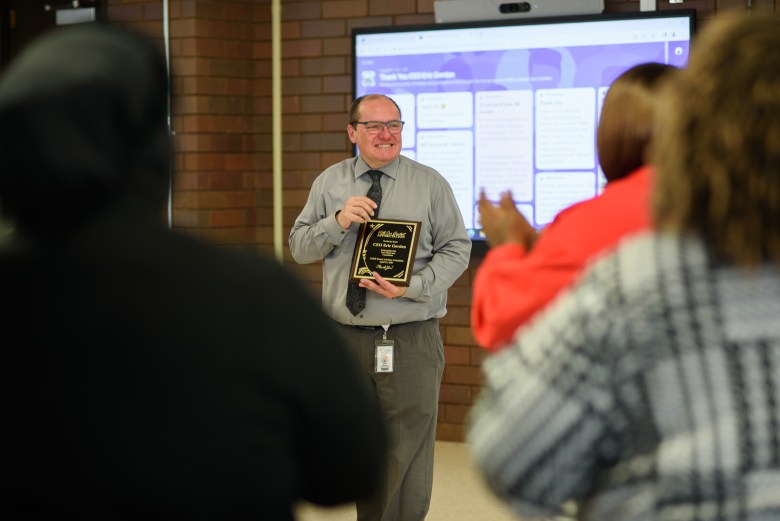

Tracy Hill, who leads the district’s family engagement work, pulls up a screen showing dozens of digital thank-you notes that the committee’s parents have written to Gordon and gives him a plaque from the group. The parents are on their feet applauding. Someone starts a chant: “Eric! Eric! Eric!”

Gordon is getting a lot of that: plaques, thank-yous, T-shirts, goodbye hugs from parents, teachers and current and former students. It’s an emotional rollercoaster, Gordon said later, trying to keep it together to finish out his last few weeks. It’s been up and down, too, for many others involved with Cleveland’s school system, who are on edge about what comes next.

By many measures, schools here made big gains under Gordon and the ambitious 11-year effort to overhaul the education system that he helped create. But the pandemic wiped out some of the improvements in academic performance and graduation rates that the district had seen under the so-called Cleveland Plan. Now, many worry that the district won’t rebound — and will head back into the cycle of rotating leadership, low performance and lack of public trust that existed before the turnaround.

A lot rides on the school system’s continued improvement: Not just student outcomes, but also the future of the city itself and the fortunes of its young, new mayor, Justin Bibb.

The effects of poverty on education make further gains a daunting challenge. Cleveland is one of the poorest major cities in the country, and research shows that family income level predicts school achievement and career success.

The graduation rate in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District rose from 56 to 81 percent between 2011 and 2020.

Schools can’t make up for lack of investment in the surrounding community on their own, say researchers. “Abject poverty in particular is a challenge to overcome,” said Raymond Hart, executive director at the Council of the Great City Schools, which represents the nation’s largest urban school systems. But sustained efforts like Cleveland’s can make up a lot of ground and have done so in cities like Atlanta, Chicago, Miami and Dallas, he added.

Still, the research on these efforts is mixed. Decades of chronic underfunding is often at the root of the struggles in districts like Cleveland to serve high proportions of Black and Latino students from low-income backgrounds, said Allison Rose Socol, a vice president at The Education Trust, an education advocacy group. “It is always, always about deep, longstanding, chronic, systemic inequities, and often racial inequities,” she said. “And so, no improvement efforts big or small in any city or district could be successful without both understanding historically how that has come to be and addressing it.”

Related: How to make Cleveland ‘great again’?

The Cleveland Plan began in the 2011-12 school year, a make-or-break time for the district. The school system, with the lowest student academic performance in Ohio, was deep in debt, had lost public trust, and the state was threatening to take it over. Then, Frank Jackson, the city’s mayor at the time, proposed that the city come up with its own plan.

He and Gordon, who’d been tapped in June 2011 as interim CEO after serving for four years as chief academic officer, pulled together a coalition of philanthropists, nonprofit leaders, local government officials and others to support the newly named Cleveland Plan.

What they devised was an all-of-the-above approach, salting in education ideas favored by liberals with those liked by conservatives. The plan would close and replace low-performing schools, including turning some over to charters; give principals more power over their own curriculums, budgets and policies; raise taxes to fund the effort; and offer high-quality preschool to all children.

The strategy was bolstered in 2019 when Gordon attracted a national college-promotion program called Say Yes. The program pays the balance of public college tuition for every student who graduates from the district, and provides support services to help them get to college — afterschool programs, tutoring, help with food, mental health and medical services, and more.

Student outcomes improved. The graduation rate rose from 56 to 81 percent between 2011 and 2020. The number of children enrolled in high-quality preschools almost doubled, the number of high-quality preschool providers tripled and kindergarten readiness improved in tandem. College-going rates increased from 44 percent before Say Yes to 49 percent after.

The efforts helped to persuade some parents, even those who could afford other options, to keep their kids in the district schools. Gesta Miller’s daughter, now a high school senior, was offered a full scholarship to a parochial school but turned it down to attend the Cleveland School of Science & Medicine, a selective district school whose curriculum better fit her interests. Another parent, Rachel Clawson, said that before the Cleveland Plan she wouldn’t have considered putting her children in a district school. Because of the improvements, her first grader attends William Rainey Harper elementary on the city’s south side.

Covid put the district’s gains in jeopardy. Performance on state tests tumbled 24 percent. The graduation rate dipped for the first time in a dozen years. Early childhood education programs were forced to cut capacity or close because of staff shortages, and the number of kindergartners on track in language and literacy fell in turn.

The proportion of chronically absent students in Cleveland schools doubled to about half of the entire student body from 2020 to 2022; students lost between 3 and 14 months of learning.

Among major cities, Cleveland was in an especially poor position to manage the pandemic, which hit low-income and Black and Latino communities the hardest. The Ohio city has the highest child poverty rate of any large city in the U.S., the lowest levels of internet connectivity and it is the eighth-most-segregated metro area in the country. The city’s high poverty and low vaccination rates made it one of the nation’s most vulnerable spots for the omicron variant of Covid that hit in late 2021.

The district had toggled between remote and hybrid instruction in 2020-21, returning to in-person classes at the beginning of the 2021-22 school year, only to ping-pong between remote and in-person learning again after omicron struck, a situation that continued for the rest of the school year. The proportion of chronically absent students doubled to about half of the entire student body from 2020 to 2022. Students lost between 3 and 14 months of learning. English proficiency fell by 8 percentage points and math proficiency by 15, with the highest declines among low-income and nonwhite students. Enrollment fell by 7 percent from the 2019-20 school year to 2020-21.

Nouh Shaikh, a 17-year-old senior at the district’s John Marshall School of Engineering, was a straight-A student until the 2020-21 school year, when he was a sophomore. The first semester that year, his whole family got Covid and he had to take care of them — cooking, cleaning, buying groceries. In the second semester, he came down with the virus. He ended up with two C’s and a D that year. Of the students he knew, perhaps 10 percent managed relatively well in that period, and he was in that small group, he said. It was far worse for students who were already struggling; he knew many who gave up and stopped coming to class.

Related: How Cleveland revamped its preschool programs in just five years

In November 2021 Justin Bibb, a first-time mayoral candidate who’d never held elective office, upended Cleveland’s political establishment, winning by more than 20 points after running a progressive campaign promising to modernize city services, reform policing and modify the culture of City Hall.

Last June, midway through his first year in office, he called for a “great reset” and faster improvement in the schools, telling a reporter that, among other things, he was dissatisfied with the large percentage of district graduates who required remediation to start college.

Bibb and the school board didn’t offer to renew Gordon’s contract. The Cleveland Plain Dealer reported that the board had been ready to renew in April but couldn’t do so without a signoff from the mayor, which the board did not get. The mayor confirmed to the Plain Dealer that he hadn’t been ready to decide in April whether he wanted Gordon to stay on and hadn’t met with him about whether they shared the same vision for schools.

In September, Gordon announced he was leaving. In an editorial, the Plain Dealer wrote that Bibb didn’t understand what an “immense loss to the district” the departure was.

Gordon said in an interview that he likely would have signed a contract renewal in spring 2022 had it been offered, but added that he’d already been thinking of leaving. Despite the damage from Covid, he wanted to hand off control to someone else while the school district was in a relatively strong financial position and had good relationships with the unions and high public trust, he said.

Bibb’s press spokesperson referred questions to Holly Trifiro, the city’s chief education officer. She said there was no decision not to keep Gordon and that the choice to leave was his. His contract wasn’t up till summer 2023 and so there was no reason to discuss renewing it last year, she said.

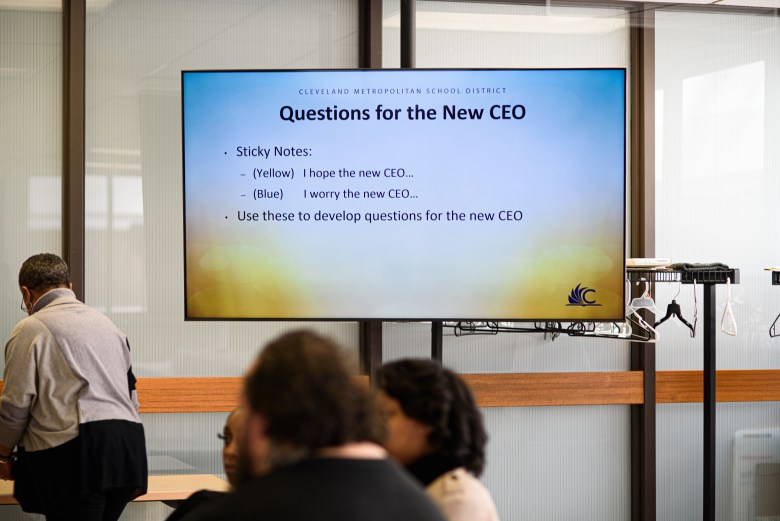

Some local leaders and educators are nervous about the mayor’s plan for schools post-Gordon. In November, the mayor issued a report on a listening tour on the school system he and his team conducted with 250 teachers, principals, parents and students.

The report acknowledged that students in several grade levels and subjects were exceeding expectations and that test scores were rebounding, but it also pointed to challenges: minimal advances in student learning since 2003, persistent achievement gaps between student demographic groups, few students ready for college at graduation. A quote from the mayor about the need to “accelerate the pace of change” in Cleveland’s schools was prominently displayed.

Cleveland Teachers Union president Shari Obrenski said she cautioned the mayor about using the term “acceleration” without acknowledging the gains of the last 11 years. “My biggest concern is that we focus too much on acceleration and not enough on where we’ve come from,” she said. Another person in the school system, who didn’t want to be named out of fear of losing their job, said they disliked the report’s tone: “Part of what I was taken aback by was, we just went through a global pandemic … I think the mayor is young. I really wish he’d taken more time to actually visit schools and really see firsthand what’s going on.”

Trifiro declined to comment on that characterization but affirmed that the administration believes the Cleveland Plan is “the right direction for our schools and our city.” In picking a new superintendent, the mayor was looking for someone who “deeply believes in the pillars of the Cleveland Plan,” she said. The mayor’s comment about a “reset” was in the context of recovery from the damage caused by Covid and doesn’t represent a desire to go in a different direction, she said.

On May 9, Bibb announced Gordon’s replacement — Warren Morgan, chief academic officer in the Indianapolis public school system. Morgan isn’t new to the district, having worked in Cleveland’s school system from 2014 to 2016 as a network leader overseeing a subset of its schools.

Discussing the future of the Cleveland Plan without Gordon, educators and parents here convey equal parts hope and fear. Behind the dueling sentiments is a question: Are the improvements Cleveland’s schools experienced before Covid due to the plan or to Eric Gordon?

“I think that where we found collaboration and success, I don’t know if I attribute it so much to the Cleveland Plan as it is Eric’s leadership,” said union vice president Jillian Ahrens. “We’re hoping for the best and preparing for the worst.”

Parents trust Gordon, in part because he “doesn’t talk down to them,” said Hill, the family engagement leader. At a recent board of education meeting, parent Teffannie Hale thanked Gordon during the public-comment period: “Every time I have called you, you have come, you have accepted my candor, you never accepted my assertion as aggression, and I appreciate that from you.”

Reflecting on Hale’s comments a few weeks later, Gordon told The Hechinger Report that in the past he’d had to intervene with those in leadership who wanted to cast her as an angry parent who would never be satisfied. “I had to say, ‘Time out. This is what we want. We want parents to advocate,’” he said.

And there are his bonds with students. Shaikh, the John Marshall senior, said that when he and a group of students were going door to door handing out letters to convince students to come back in person, Gordon was there with them knocking on doors.

Related: Who wants to lead America’s school districts? Anyone? Anyone?

Even as Gordon leaves, there are reasons for optimism. Hill is excited about the choice of Morgan as superintendent. She worked with him in his prior role with the district. “He’s a wonderful person. He has proven leadership,” she said. She watched him interact with parents during the interview process and said he seemed to form a very quick bond with them. Gordon, who hired Morgan for his prior role, said he has the “professional humility to understand that there are no quick silver bullet solutions to really complex problems.”

The district is starting to bounce back post-Covid. Student scores on state tests rose 42 percent between the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years. Last September, the district re-launched a campaign to cut the sky-high truancy rate. Parents received calls if their child missed consecutive days, but were also offered help with transportation, health care or other needs.

Longer term, Gordon points to the gains the schools have made despite the city’s high poverty rate, which hasn’t budged over the Cleveland Plan’s 11 years. “I would be the first to say we haven’t gotten enough progress. But we did all that in spite of the larger conditions,” he said. “If we’re really going to get the results that we want for our community, we must get at the disruption of these larger persistent things and particularly in dense, generational poverty.”

Cleveland’s public still buys into the plan. In November 2020, in the teeth of the pandemic, a referendum to raise property taxes to fund the schools won by more than 20 points — the third such vote in favor of increased taxes for education since the Cleveland Plan went into place. Voters “understand that there’s a ways to go, but … they believe in the system, they believe in the direction,” said Helen Williams, program director at the Cleveland Foundation, which funds parts of the plan and runs polls on education issues.

That support may be key to the plan’s success once Gordon leaves. In other efforts around the country to change the shape of education, the loss of a leader is indeed a challenge, said Socol, of The Education Trust. But when there’s community consensus, “there’s a much greater chance those things will be sustained than if it was just a big dream of one individual,” she said.

On May 26 Cuyahoga Community College, which has campuses in and around Cleveland, announced it’s hiring Gordon for a new position as a senior vice president tasked with identifying and addressing gaps in the college’s student support systems. He’ll also design new approaches to helping students transition from early childhood through post-secondary education and early career as part of a new strategy at the college.

“I have said no to a lot of things, and I fully expected to say no to [this role] as well,” said Gordon. “And I found myself saying, ‘This is the stuff I love — figuring out coherence, advocating for students.’”

And though some fear worse times are ahead for Cleveland’s schools, others say there’s a solid foundation for the district to keep improving. “It’s always an uncertain time when leaders transition,” said Kara Porter, executive vice president of Starting Point, a nonprofit that supports children and families in northeast Ohio. But having the Cleveland Plan’s infrastructure will ensure that the community stays together on it: “That’s the gift Eric Gordon has given this city,” she said.

This story about the Cleveland Plan was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.