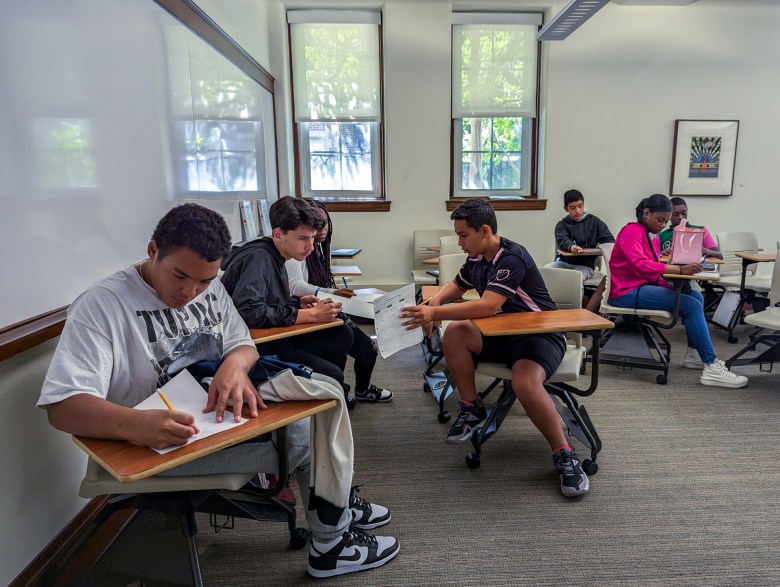

BROOKLINE, Mass. — It was a humid, gray morning in July, and most of their peers were spending the summer sleeping late and hanging out with friends. But the 20 rising 10th graders in Lisa Rodriguez’s class at Brookline High School were finishing a lesson on exponents and radicals.

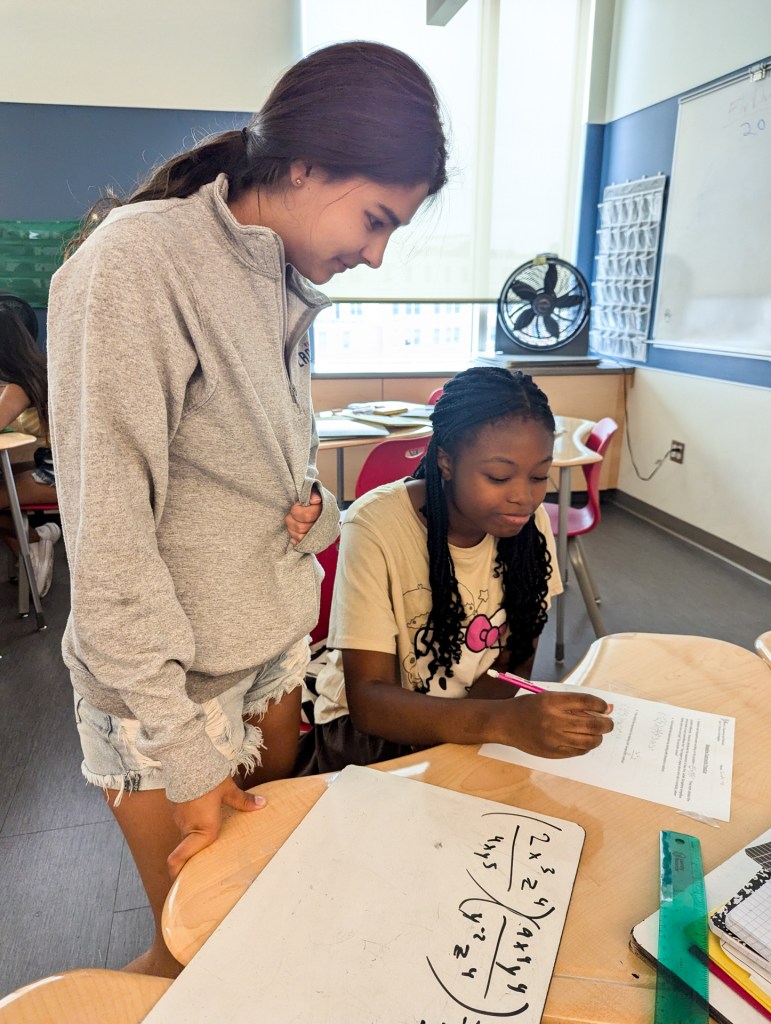

As Rodriguez worked with two students on a difficult problem, Noelia Ames was called over by a soft-spoken student sitting nearby. Ames, a rising senior who took Algebra II Honors with Rodriguez as a sophomore, was serving as a peer leader for the summer class.

“Are you stuck on a problem?” Ames asked, leaning over to take a closer look.

The students in Rodriguez’s class were participating in a summer program created by the Calculus Project, a Massachusetts-based nonprofit. Founded at Brookline High near Boston in 2009, the group now works with roughly 1,000 students from 14 nearby districts beginning in the summer after seventh grade to help them complete advanced math classes like calculus before they finish high school.

It focuses on helping students who are historically underrepresented in high-level math classes — namely those who are Black, Hispanic and low-income — succeed in that coursework, which serves as a gateway to selective colleges and well-paying careers. While some states and districts are nixing advanced-math requirements, sometimes in the name of equity, the Calculus Project has a different theory: Students who have traditionally been excluded from high-level math can succeed in those courses if they’re given a chance to preview advanced math content over the summer and take classes with a cohort of their peers.

In recent years the Calculus Project’s work has taken on fresh urgency, as the pandemic hit Black, Hispanic and low-income students particularly hard. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court ruling banning affirmative action left even some college officials concerned that inequities in high school math would make it harder for them to fill their classes with students from diverse backgrounds. The Calculus Project’s national profile has grown — its staff advises the College Board on AP math exams and classes and have advised groups in a few other states — even as the organization has attracted some scrutiny from parents, due to its emphasis on students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“One out of 10 Black students in the eighth grade math scores were scoring basic or above,” saidKristen Hengtgen, a senior policy analyst at the nonprofit advocacy group EdTrust, referring to last year’s National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as the Nation’s Report Card. “When you see that, you need to throw certain student groups the life jacket,” she added. “We cannot combat a math crisis if we’re not helping the students who need it the most.”

Related: Widen your perspective. Our free biweekly newsletter consults critical voices on innovation in education.

The racial and socioeconomic gaps in math are stark: Only 28 percent of Black students and 31 percent Hispanic students nationwide took advanced math in high school compared with 46 percent of white students, according to a 2023 report from EdTrust. Just 22 percent of low-income students took advanced math. Experts say that’s because these students are less likely to attend high schools that offer higher-level math or to be recommended by their teachers for honors or AP classes, regardless of mastery.

They are also less likely to report feeling confident in math class or to enroll in calculus even when they are on a path to take the class early in high school, according to a report from EdTrust and nonprofit Just Equations. When it comes to Black and Hispanic students, Hengtgen blames what she calls “the belonging barrier.” “Their friends weren’t in the class,” she said. “They rarely had a teacher of color.”

As a math teacher at Brookline High in the early 2000s, Calculus Project founder Adrian Mims got firsthand experience in what the research was beginning to establish. Black and Hispanic students were largely absent from the high school’s honors and advanced math courses, he said, and the few Black and Hispanic students who did enroll often dropped out early in the year.

As a PhD candidate at Boston College, Mims was writing his dissertation on how to improve African American achievement in geometry honors classes. His findings — suggesting that Black students dropped out of the course because they lacked knowledge of certain foundational math content, spent less time studying and preparing for tests, and lacked confidence in their math ability — became the catalyst for the first iteration of The Calculus Project.

Mims’ idea was to introduce Black students over the summer to math concepts they’d learn in eighth grade algebra in the fall. Students would be able to take the time to really understand those concepts and to build their confidence and skills, learning both from district teachers and peer teachers who could provide individual support.

In the summer of 2009, Mims piloted his idea with a group of rising eighth graders. In addition to learning concepts they’d see in algebra that fall, they were exposed to the stories of famous Black and Latino figures who excelled in STEM, such as Black NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson and Mexican-American astronaut Jose M. Hernandez. When the school year arrived, they participated in after-school tutoring at Brookline High.

The next fall, 2010, the district opened the program to all interested students, regardless of race. Summer participants were placed into cohorts so they could advance through math classes in high school with peers they knew.

Teachers and administrators at Brookline say the project had an immediate — and lasting — impact. “It’s so much more than learning math,” said Alexia Thomas, a guidance counselor and associate dean of students at Brookline High.

In 2012, Brookline High saw more Black students score as advanced on the state Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System Math test than ever before; 88 percent of those students had participated in the Calculus Project. The highest-scoring student in the district was Black – and a program alum. Two years later, when the first cohort of students who participated in both the summer and year-long programs graduated from high school, 75 percent had successfully completed calculus.

Today, eight districts participate in the year-round program and another six send their students to the group’s summer programs, two three-week sessions that take place at Boston University, Emmanuel College and University of Massachusetts-Lowell. As of May 2024, 31 percent of students in the program identified as Black, 39 percent as Hispanic/Latino, 11 percent as Asian and 7 percent as white, according to program data. Mims has helped develop similar models in Florida and Texas.

In 2023, research consultancy group Mathematica, in partnership with the Gates Foundation, published findings from a two-year study on the effectiveness of the Calculus Project and two other math-oriented summer programs. (Disclosure: The Gates Foundation is one of the many funders of The Hechinger Report.) According to the report, students in the Calculus Project outperformed students who hadn’t participated by nearly half a grade point in their fall math classes, on average.

Related: Data science under fire: What math do high schoolers really need?

The project runs counter to a recent push to engage high schoolers in math by making the content more relevant to the real world and substituting classes like data science for algebra II and calculus. Justin Desai, the Calculus Project’s director of school and district support and a former Boston Public Schools math teacher and curriculum designer, said he sees risks in that approach. Students need subjects like calculus, he said, because “it’s the foundation of modern technology.” To replace advanced math classes in favor of less rigorous math courses keeps students from accessing and excelling even in some non-STEM fields like law, he said.

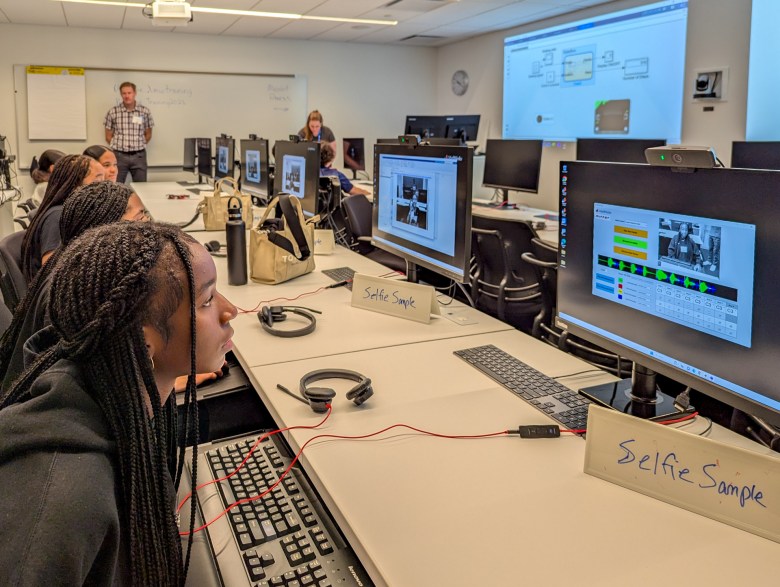

The project finds ways to show students how math skills apply in the professional world. Every semester students take field trips to Harvard Medical School, Google and to university research centers and engineering companies, where they are introduced to careers and see how the math they are learning is used in society.

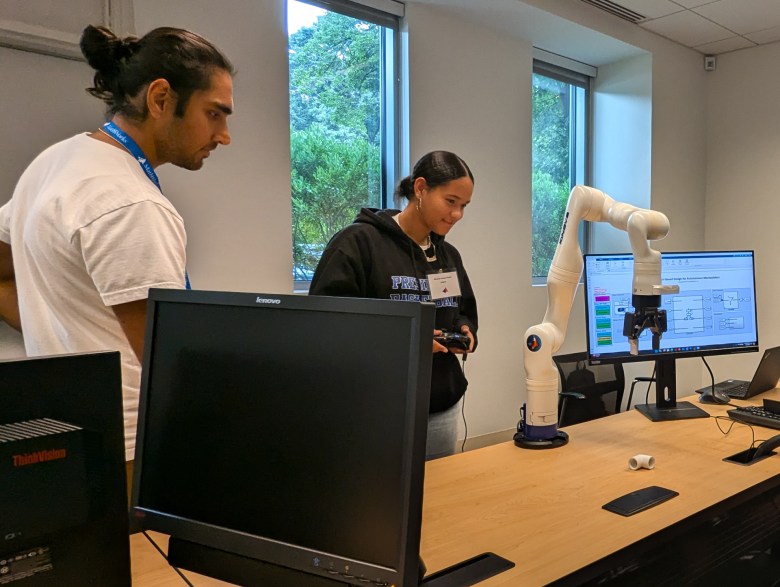

In late July, a group of rising eighth graders from Newton Public Schools’ summer program took a field trip to the sprawling campus of global software company MathWorks. In one room, an engineer showed students how a car simulation model is built and used, while a second engineer helped students test a robotic arm. Another group of students learned how to use a programming software to turn an image into music.

As the Calculus Project has grown, there has at times been friction. In July, simmering tension between teachers and students at Concord-Carlisle High School came to a head when some project participants learned they’d been placed in financial literacy or statistics courses instead of calculus.

Some students being placed into lower-level classes has been a pattern since the program started at Concord-Carlisle in 2020, Mims said. He threatened to pull the program from the high school, and the students were reassigned to calculus (and one to statistics).

Mims said “this is a clear example” of how teacher recommendations can lock students out of advanced math classes. School administrators and teachers often point to students and parents as the reason for a lack of diversity in high-level math. “When we destroy that myth and we show that students can achieve at that level,” said Mims, “they can no longer point the finger at the students and the parents anymore, because we’ve created a precedent that these students can thrive.”

Laurie Hunter, the Concord-Carlisle superintendent, wrote in an email that her district is committed to partnering with the Calculus Project and that it “works closely with individual students and families to ensure their success and path align with the outcomes of the project.” She did not respond to specific questions.

Milton Public Schools, another district that works with the Calculus Project, was the subject of a 2023 federal civil rights complaint from national conservative group Parents Defending Education. The group accused the district of discrimination by partnering with the Calculus Project, which it said segregates students by intentionally grouping students of certain backgrounds together as part of cohorts.

Mims rejects the group’s claims, noting that the Calculus Project is open to students of all backgrounds including white and Asian students. He says he has not heard from the federal government or the group about the complaint since early 2023. Parents Defending Education did not respond to several interview requests. A spokesperson for the federal Department of Education said the Office for Civil Rights does not confirm complaints but pointed to its list of open investigations. At the time of publication, there were no open investigations against Milton Public Schools.

Art Coleman, a founding partner at legal group EducationCounsel LLC, said that he doesn’t expect such challenges to be successful. School districts have a legal obligation to address inequities in student performance, he said, and “there is nothing in federal law that precludes that targeted support, as long as in broad terms, all students, regardless of their racial or ethnic status, have the ability to tap into those resources and that support.”

Related: How one district has diversified its advanced math classes — without the controversy

This summer, the Calculus Project expanded its programming, including by adding a college advising class for rising seniors. It’s part of the group’s mission to help its students succeed not just in high school but in college and beyond, Mims said.

The group plans to help its graduates secure internships while they’re in college and network once they’re out, he said, and will soon begin tracking students to see how they do in college and the workforce. “It’s really about giving them every advantage that rich kids have,” Mims said.

Ames, the Brookline High senior and peer teacher, said she has found the program “totally life-changing,” in part because of the relationships she’s built with other students and teachers.

“You can be in the hardest class or the easiest class and every teacher will be there to support you,” said Ames, who is taking AP Calculus this fall and is considering studying finance after high school. “Whatever questions you have, they’ll answer.”

Quentin Robinson, a college junior who joined the Calculus Project as a rising seventh grader, said it taught him that he enjoyed math and also how to advocate for himself.

“My freshman year, they tried to put me in a lower-level math class because they didn’t think I was capable,” Robinson said. But his summer experience empowered him, and he persuaded the school to place him in Geometry Honors instead. He graduated from high school having completed both calculus and a college-level statistics course.

Now, Robinson is an accounting and data analytics major at Stonehill College in Easton, Massachusetts. The Calculus Project, he said, helped him realize the voices of naysayers can be used as “a fuel” to achieve what you want.

Contact staff writer Javeria Salman at 212-678-3455 or salman@hechingerreport.org.

This story about advanced math was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our newsletter.