EWING, N.J. — Bethany Blonder and her friends lined up at the voter information table in the student union before organizers had even finished setting it up in time for lunch.

It’s true that a fire drill had chased them there from their dorm on the campus of The College of New Jersey, or TCNJ. But the women were also quick to rattle off what they see as the existential issues that make them hell-bent on casting their ballots in the general election.

Climate change, for instance.

“All of our lives are at risk — our futures — and the lives of our neighbors, the lives of our friends,” said Blonder, a freshman from Ocean Township, New Jersey. “Every time there’s a hot day outside, I’m, like, is this what it will be like for the rest of my life?”

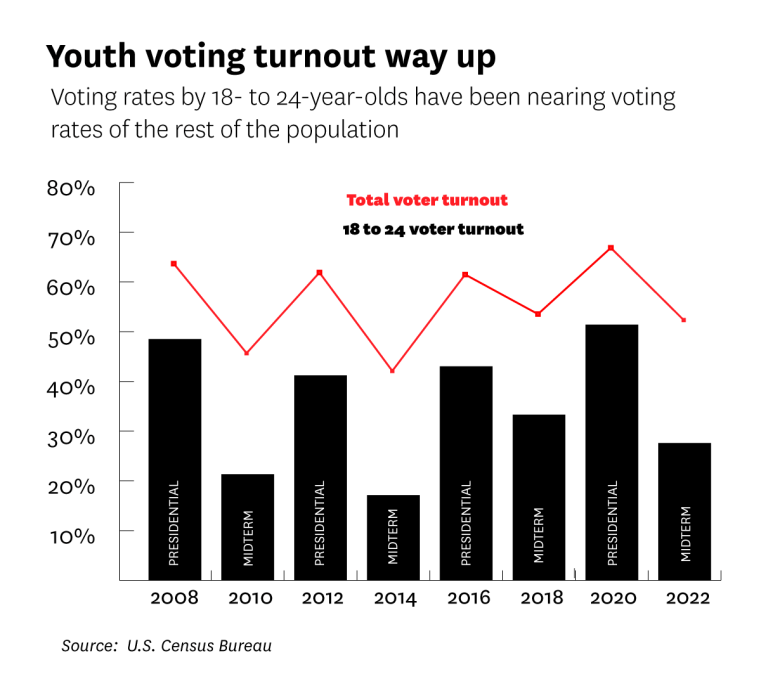

Americans ages 18 to 24 have historically voted in very low proportions — 15 to 20 percentage points below the rest of the population as recently as the presidential election years of 2008 and 2012, with an even bigger gap in the 2010 midterms, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But rates of voting by young people have quietly been rising to unprecedented levels, despite their lifetimes of watching government gridlock and attempts in some states to make it harder for them to vote.

More than half of Americans ages 18 to 24 turned out for the 2020 general election, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. That proportion was up by more than 8 percentage points from 2016, and has been closing in on the voting rate for adults of all ages. Among college students, the proportion who voted was even higher.

Young people say that they’re propelled by concerns that directly affect them, such as global warming, the economy, reproductive and LGBTQ+ rights, student loan debt and gun safety.

As early as elementary school, “we grew up having to learn about lockdowns” in response to mass shootings, said Andrew LoMonte, one of the students staffing the voter table. “What people are realizing is that the issues the candidates are talking about actually matter to us.”

The political division they’ve witnessed hasn’t discouraged young voters, said LoMonte, a sophomore political science major from Bloomfield, New Jersey, who was wearing a “TCNJ Votes” T-shirt. It’s made them more determined to become involved.

“You’d think the dysfunction would scare people off, but it’s a motivator,” LoMonte said.

Sixty-six percent of college students voted in 2020, up 14 percentage points from 2016, according to the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement at Tufts University’s Institute for Democracy and Higher Education.

Younger students ages 18 to 21 voted at the highest rates of all, portending a continued upward trend, the study found.

“You’re seeing a generation of activists. I mean, very young — 16, 17,” said Jennifer McAndrew, senior director of communications and planning at Tufts’ Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life. “It goes back to them engaging each other and saying, ‘This isn’t a perfect system. But the only way we can change it is by voting.’ ”

This is already showing some results.

Young voters had “a decisive impact” on Senate races in 2022 in battleground states including Wisconsin, Nevada, Georgia and Pennsylvania, according to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, or CIRCLE, which is also based at Tufts.

Youth voter registrations have particularly soared in states considering referenda relating to abortion restrictions. And college students were widely credited last year with helping elect a liberal candidate to the Wisconsin state Supreme Court, which is due to take up two major abortion cases.

After seeing results like those, “young people have become more aware of their own political power within states and districts,” McAndrew said.

They have also registered and voted at high rates in several swing states. Michigan had the biggest turnout in the country of voters 30 and under in 2022 — 36 percent — according to CIRCLE. Young people in Pennsylvania have turned out at above-average rates in the last three presidential races.

The nonpartisan voter registration group Vote.org reports that it has registered a record 800,000 voters under 35 in time for the November general election. Of the more than 1 million new voters it signed up in all, Vote.org says 34 percent were 18, compared to 8 percent during its 2020 voter registration drive.

The Big Ten Conference runs a voter turnout competition that has increased student voter turnout at member schools. The organization People Power for Florida held its fourth annual “Dorm Storm” for students at eight universities in August and registered 728 new voters during move-in week, the most ever, the group said.

Both presidential campaigns are using social media and targeting students on college campuses in pivotal states. The Democratic National Committee has hired banner-towing airplanes to fly over college football games on behalf of Democrat Kamala Harris, while Republican Donald Trump has a TikTok account and has courted social media influencers.

And Taylor Swift’s recent endorsement of Harris and call to her fans to register and vote helped drive over 24 hours a more than 20-fold increase in visitors to the federal government website Vote.gov, which provides voter registration information. “If you are 18, please register to vote,” Swift later said at the MTV Video Music Awards. “It’s an important election.”

McAndrew gives particular credit for the rising numbers of young voters to the gun-safety organization March for Our Lives, founded by survivors of the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Parkland, Florida, that killed 17.

“They have led protests, of course,” she said. “But they have also said, ‘Here’s how you call your state rep. Here’s how you call your state senator. Here’s how you register to vote.’ ”

None of these things mean that high youth voter turnout in November is assured. The proportion of college students who voted in the 2022 midterms was down from the record set in 2018. An analysis by CIRCLE shows that, for all of the enthusiasm and organizing, voter registration among Americans under 30 in most states so far is behind where it was around this time in 2020.

Meanwhile, several states have imposed restrictions that affect student voting, limiting polling locations, voting hours, absentee voting, ballot boxes and the use of student IDs to vote. A survey in 2016 found that one in five students who were registered to vote but didn’t cast ballots said it was because they had issues with or didn’t think they could use their IDs. (State student ID laws for voting are listed in The Hechinger Report’s “College Welcome Guide.”)

Related: Beyond the Rankings: The College Welcome Guide

“Even when young people would have been able to vote, they sometimes tell us they didn’t even try because they thought they needed another kind of ID,” said McAndrew, at Tufts.

A new law in Florida imposes strict limits on third-party organizations, including student groups, that try to sign up new voters. The law imposes fines of up to $250,000 if these groups fail to follow a list of rules that include registering with the state’s elections division.

Although a little-known federal rule requires colleges and universities that accept federal money to encourage voting, universities in some states are newly fearful of antagonizing legislatures that have targeted campuses over anything that could be considered political.

“We have seen some places where they’re a bit more cautious and changed their approach a little bit to make sure they’re doing everything by the book,” said Clarissa Unger, co-founder and executive director of the Students Learn Students Vote Coalition, which includes about 350 nonpartisan voting advocacy groups. “There are certain states where it’s become much harder, and those are states a lot of our organizations are focused on even more.”

Not all groups of students vote in equally high numbers. Seventy-five percent of students at private, nonprofit colleges voted in 2020, for instance, compared to 57 percent at community colleges. Students majoring in education, social sciences, history and agricultural and natural resources turned out at the highest rates; those in engineering and technical fields, at the lowest.

“Engineering is really difficult and there’s a lot of heavy coursework,” said Liora Petter-Lipstein, a senior public policy major at the University of Maryland, who set out to learn why engineering students there voted at lower levels than their classmates. “They don’t really have time for other things and voting doesn’t become a priority.”

Many young Americans also still don’t see the point, Petter-Lipstein said.

“A lot of people said they didn’t think their vote matters. They don’t feel informed enough to vote, they missed the ballot request deadline or they say, ‘Oh, I’m just not a political person.’ I was talking to a friend of mine who happens to be an engineer who didn’t even realize that they could vote in Maryland.”

To them, she tries to connect the election with issues of interest.

“A lot of what we’ve been focusing on has been, ‘Hey, did you know that these things are on the ballot?’ ” That includes, in Maryland, a referendum to add the right to an abortion to the state constitution’s declaration of rights.

Related: ‘We’re from the university and we’re here to help’

At TCNJ, more than 83 percent of students voted in 2020, putting the college in the top 20 among higher education institutions nationwide, according to the nonprofit Civic Nation, which advocates for people to vote.

First-year students here are required to take a community service course, there’s a voter registration contest among residence halls, and students get text reminders about voting deadlines. TCNJ, just outside the capital of Trenton, is also part of a voting competition with other New Jersey campuses, called the Ballot Bowl.

Even before they arrive, however, students are politically active, said Brittany Aydelotte, director of the school’s Community Engaged Learning Institute.

“They’re really coming in with much more knowledge about social justice issues,” Aydelotte said. “Social media has a huge impact. They’ve been able to figure out how [politics] relates to them personally. Our goal is that they leave here thinking, ‘Hmmm, what else can I do?’ ”

The polarized politics of the times makes students even more eager to create change, said Jared Williams, the president of TCNJ’s student government.

“It’s not enough to throw our hands in the air and give up,” said Williams, a senior political science major from Union, New Jersey. “It’s very easy to get disillusioned. But there’s no way to end that cycle if you don’t vote.”

Besides, added his vice president for governmental affairs, Aria Chalileh, who is also a senior majoring in political science: Students “are realizing that these issues are being talked about. They aren’t issues that might affect them 50 years down the line. They affect them right now.”

That’s what brought freshman Roman Carlise to the line at the voter registration table, he said.

The political skirmishing of this election season “gets on my nerves,” said Carlise. “That bothers me — seeing people bicker when they’re supposed to fix the problems.”

But he planned to vote anyway, he said.

“I’m just not the type to say there’s nothing I can do.”

Contact writer Jon Marcus at 212-678-7556 or jmarcus@hechingerreport.org.

This story about college student voting rates was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our higher education newsletter. Listen to our higher education podcast.