Her face solemn, Kati Preston held up a postcard-sized, black-and-white photograph, moving it slowly to face the 150 high school students spread across the lecture hall in New Hampshire. She wanted them all to see the image of her father, a handsome man in a dapper suit jacket, as she described searching for him with her mother at a train station in Hungary in 1945.

“We stood up on the platform,” Preston said, “and we were holding a picture of my father like this, saying to everybody who got off the train, ‘Have you seen this man?’ ”

Preston, then 6 years old, stood with her mother at the station in Nagyvárad, waiting for a train carrying Jews back from concentration camps after the end of World War II. They hadn’t seen her father, Ernest Rubin, for over a year. “The train emptied, and there was no Daddy,” Preston recalled. “My mother started to cry, and I cried.” The rapt assembly of students and teachers at Kingswood Regional High School in Wolfeboro listened in silence.

Preston and her mother returned to the train station the next day, holding up the photo again. This time, a man getting off the train walked up to them. “Don’t wait for him,” he said, explaining he’d been held prisoner in the Auschwitz death camp with Preston’s father. “He’s dead.”

‘We must talk about this real history’: Reactions to ‘divisive concepts’ ban

A battle over New Hampshire’s “divisive concepts law” has been brewing in the state since 2021. The measure restricts instruction on topics that might leave students feeling inferior or superior based on race, gender, ethnicity, or another attribute, and also applies to training done by state agencies.

Earlier this year, state lawmakers proposed a repeal, eliciting more than 1,000 letters to the House Education Committee. The Hechinger Report, in partnership with The Boston Globe Magazine, analyzed a 264-letter sample to get a sense of both sides.

Preston and her mother were the only ones among their 29 Jewish relatives to survive the Holocaust, the persecution and murder of 6 million Jews. The Nazis also killed millions of other people, including gay men, political prisoners, Soviet prisoners of war and people with disabilities. Preston’s mother was born Catholic and had converted to Judaism, so the Nazis didn’t consider her Jewish, only her daughter.

For more than a decade, Preston, now 84 and the author of the young adult graphic memoir “Hidden: A True Story of the Holocaust,” has been invited to 50 to 70 middle and high schools a year to share her story. She speaks primarily in New Hampshire, her home of 40 years. Last spring, she started becoming more political in her talks, especially about the dangers of staying silent when others are scapegoated. “Ten percent of people are

very good people, wonderful people. Ten percent are pretty awful. Eighty percent are sheep, and that’s what scares me,” Preston told the students at Kingswood Regional High. “It’s the sheep that allowed Hitler to rise.”

“It’s the sheep that allowed Hitler to rise.”

Kati Preston, Holocaust survivor who lobbied for New Hampshire’s Holocaust education law

Preston speaks frankly about the politicization of history instruction. “You have to know your history to understand where you are coming from. Don’t let them distort it,” she urges the teens, whose school of around 700 students draws from a mix of towns — poor and wealthy, conservative and liberal-leaning. She cautioned them not to let people “change your laws to stop you learning about history.”

New Hampshire schools have become battlegrounds in the culture wars over racism and gender identity, and comprehensive education on the Holocaust is in danger, experts and teachers say. In 2020, after events including the mass shooting two years earlier that killed 11 people at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, New Hampshire passed a law requiring instruction on the Holocaust and other genocides in grades 8 through 12. But then, in 2021, as part of a backlash to the nation’s racial reckoning after the murder of George Floyd, New Hampshire banned the teaching of “divisive concepts” such as implicit bias and systemic racism.

Kati Preston, a Holocaust survivor and education speaker, at her home in New Hampshire. Credit: Vanessa Leroy for The Boston Globe

Now these two laws are colliding in the state’s classrooms. Some of the topics that the divisive concepts laws restrict are precisely the ones that Holocaust education experts say must be covered to prevent a repeat of history. A key part of teaching about the Holocaust and other genocides is examining how one group of people could agree to participate in the mass murder of another. The answer, in part, lies in the use of propaganda that asserts one group as inferior. Adolf Hitler modeled his depiction of Jews as an inferior race on America’s racist treatment of Black people and the study of eugenics in this country.

Letters of concern to the New Hampshire Legislature and interviews with teachers reflect that, in teaching about the Holocaust, many feel scared to discuss certain topics as a way to draw contemporary parallels because of the state’s divisive concepts law.

Kingswood social studies teacher Kimberly Kelliher is among them. She says the state’s reporting mechanism for parents to accuse teachers of violating the law — plus a monetary award offered by the parent activist group Moms for Liberty aimed at encouraging such reports — frightens her. “The Holocaust is not a single event. It is a series of attitudes and actions that led to an atrocity,” says Kelliher, who has taught social studies for more than two decades. “When we look at the divisive concepts law, if we are denying people from talking about certain things, then we’re not honestly talking about the attitudes and actions.”

“The Holocaust is not a single event. It is a series of attitudes and actions that led to an atrocity. When we look at the divisive concepts law, if we are denying people from talking about certain things, then we’re not honestly talking about the attitudes and actions.”

Kimberly Kelliher, social studies teacher, Kingswood Regional High School

Kelliher, like other teachers I spoke with, said she now avoids the word “racism” when talking to students about the Holocaust. Others say they avoid mentioning current events and hot-button topics such as implicit bias.

But a New Hampshire scholar says it’s impossible to avoid subjects like these if we truly want to learn from the atrocities of the past. “You can’t teach about Nazi perpetrators without teaching about implicit bias. You just can’t do it. What motivates the perpetrator?” says Tom White, the coordinator of educational outreach at Keene State College’s Cohen Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Hitler took advantage of implicit bias and conspiracy theories against Jews that had existed through thousands of years of antisemitism. “The central crux of fascism is to make their followers afraid that they’re under attack by another group, that they’re threatened by another group,” White says. “Implicit bias,” he adds, “is the crux of all of this.”

Preston advocated tirelessly for New Hampshire’s Holocaust education law. It mandated that, beginning last school year, education on the Holocaust and other genocides start no later than eighth grade and be incorporated into at least one required high school social studies course. New Hampshire is one of 26 states with such a law, according to Echoes & Reflections, a Holocaust education organization. Massachusetts passed a law in 2022 establishing a fund to support genocide education and training; laws requiring Holocaust education now exist in every other New England state except Vermont, where one has been introduced.*

Under New Hampshire’s law, instruction must include facts about the Holocaust and other genocides, plus teach students “how and why political repression, intolerance, bigotry, antisemitism, and national, ethnic, racial, or religious hatred and discrimination have, in the past, evolved into genocide and mass violence.” Teachers, state Department of Education guidelines say, should help students “identify and evaluate the power of individual choices” in preventing such behavior.

Reports of antisemitic incidents and propaganda are on the rise nationally and regionally, according to the Anti-Defamation League of New England. In 2022, the nonprofit tracked 204 antisemitic incidents in New England, a 32 percent increase from the previous year. In New Hampshire, where 183 of those incidents took place, the spike of white supremacist propaganda activity included a classmate shouting antisemitic comments at a Jewish student; a swastika and the phrase “Kill all Jews” scrawled on a rock in a public place; and a neo-Nazi group distributing stickers with the Star of David and message “Resist Zionism.”

In 2021, a year after New Hampshire’s Holocaust and genocide education act became law, the state Legislature tucked into its budget bill an unrelated provision called “Right to Freedom from Discrimination in Public Workplaces and Education.” Known informally as the “divisive concepts law,” it’s part of a wave of “anti-woke” legislation around the country that right-wing backers have identified as a way to politically capitalize on white resentment and the concern by some people that white children are being made to feel guilty about segregation and other past racial injustices.

The divisive concepts law in New Hampshire prohibits students from being “taught, instructed, inculcated or compelled to express belief in or support” that someone is “inherently superior” to another based on a particular trait, including sex, race, and religion, and also states that students cannot be taught that an individual is “inherently racist, sexist or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.” Educators who run afoul of this provision can face sanctions, including loss of their teaching licenses.

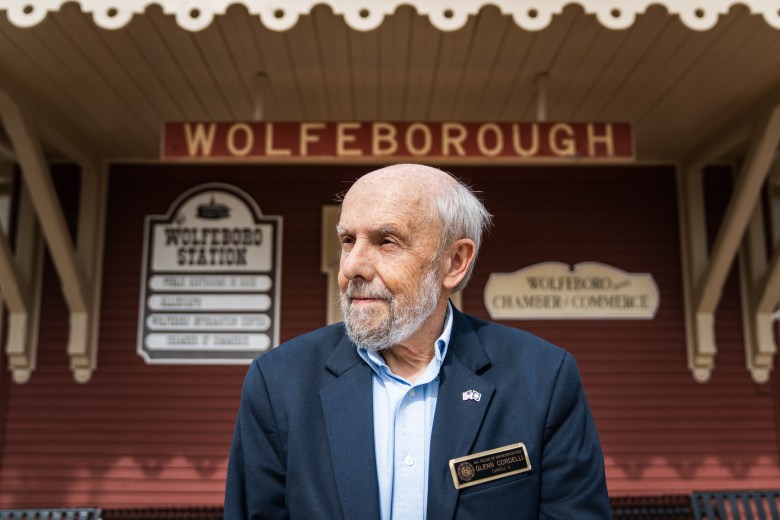

“The whole concept of race superiority and guilt over the past is concerning.”

Republican state Representative Glenn Cordelli, vice chair of the House Education Committee, who cosponsored New Hampshire’s initial divisive concepts bill

Republican state Representative Glenn Cordelli, vice chair of the House Education Committee, cosponsored New Hampshire’s initial divisive concepts bill, which failed to pass as a standalone law. I met him for breakfast at Katie’s Kitchen in Wolfeboro in March. A soft-spoken 74-year-old, retired from a career in information technology, he lives in Tuftonboro, a feeder town for Kingswood High. His inspiration for the measure had come from a 2020 executive order signed by then-President Trump (later rescinded by President Biden) prohibiting federal funding for training that promotes the concepts, as the executive order put it, “that some people, simply on account of their race or sex, are oppressors; and that racial and sexual identities are more important than our common status as human beings and Americans.”

Cordelli told me he was concerned about teachers indoctrinating students and schools promoting critical race theory. That legal theory, which emphasizes that racism is systemic and therefore embedded in U.S. policies and programs, has been a focus of the latest wave of conservative attacks on public education, even though it’s not commonly taught in K-12 schools.

“The whole concept of race superiority and guilt over the past is concerning,” Cordelli said, citing a complaint and resignation from a Manchester public school employee over training that discussed white privilege. (“I question,” Cordelli added, “whether there is systemic racism in New Hampshire.”)

Cordelli, who voted for the Holocaust and genocide education requirements, thinks teachers should not make direct connections to ideas such as implicit bias or systemic racism when teaching about the Holocaust. Rather, he believes that in open discussion, students can connect the dots between the past and present themselves without their teachers drawing conclusions for them.

He emphasized that he thought the Holocaust education law and the divisive concepts law are not in conflict with one another. No one testifying before the education committee had “link[ed] instruction of the Holocaust with the divisive concepts bill” before it passed, he said. “That has not come up as an issue for teachers.”

But teachers and others around the state disagree with that point of view. The state’s two largest teacher unions are suing the New Hampshire education commissioner, the attorney general, and the head of the human rights commission to repeal the divisive concepts law, citing the chilling effect it is having on teaching. Deb Howes, president of the American Federation of Teachers-New Hampshire, says the law’s title, which includes the words “Right to Freedom from Discrimination,” is downright Orwellian in its doublespeak, given the law itself “is in effect chilling speech on the very concept of discrimination against various marginalized groups.”

“The divisive concepts law is so broadly worded. None of us are teaching that anyone deserves to be inherently oppressed, but we also know that when you’re talking about either history or the impact of history on current events, there are people who are oppressed and it comes from somewhere.”

Deb Howes, president of the American Federation of Teachers-New Hampshire

The vagueness of the divisive concepts law is one of teachers’ biggest concerns, Howes adds. “The divisive concepts law is so broadly worded. None of us are teaching that anyone deserves to be inherently oppressed, but we also know that when you’re talking about either history or the impact of history on current events, there are people who are oppressed and it comes from somewhere,” she says.

Many teachers I spoke with worry about parents reporting them. Some have seen this atmosphere building for years. One New Hampshire assistant principal recalled an incident from more than a decade ago that happened to her while she was teaching: a parent overheard her say the word “Nazis” and reported her to the principal. But she was, in fact, leading a lesson about the diary of Anne Frank.

In November of 2021, the New Hampshire chapter of the group Moms for Liberty tweeted an offer of a $500 bounty to the first person who caught a teacher breaking the divisive concepts law. Tiffany Justice, the Florida mother of four who cofounded Moms for Liberty, emphasizes that her group targets the teaching of CRT, and the divisive concepts law has no effect on teaching about the Holocaust. “The idea the Holocaust couldn’t be taught in its entirety with all honest truth is a ridiculous thought,” she told me. “This is a manufactured argument.”

In November 2021, New Hampshire’s education department posted an online form for people wanting to lodge complaints against teachers. Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut was concerned about teachers “trying to impose a value system on impressionable youngsters,” according to an April 15, 2022, news release (Edelbut declined to comment for this article, through a spokesperson).

Since November of 2021, only one charge related to the divisive concepts law has been filed against a teacher, the state said in response to a Hechinger Report/Boston Globe Magazine public information request. (The state human rights commission, which fields complaints against teachers under the divisive concepts law, declined to provide further information, citing its confidentiality rules regarding complaints.)

Meanwhile, many school districts, including Governor Wentworth Regional School District, where Kingswood is located, have received freedom of information requests from people wanting to know if particular books were being used and asking to see all curricula or teaching materials with particular words, including “justice” and “diversity.”

“Clearly, there are individuals and groups that are racist, homophobic, misogynistic. We can’t call them out for it?”

New Hampshire State Representative Peter Petrigno

In January, Democratic lawmakers in New Hampshire proposed a bill to repeal the divisive concepts measure, citing the chilling effect and the upheaval the current provision has already caused among educators. “I’m a German historian,” said state Representative Nicholas Germana, a professor at Keene State, during a public hearing earlier this year. “I can’t imagine for the life of me that a [measure] like this would be introduced in Germany today.”

In March, the proposed repeal died in the House. State Representative Peter Petrigno, its prime sponsor and a Democrat, said he was doubtful it ever would be passed, given the Legislature’s Republican majority, but he pledged to keep trying. “Clearly, there are individuals and groups that are racist, homophobic, misogynistic. We can’t call them out for it?” says Petrigno, a former social studies teacher. “I don’t know how you can have a lesson on the Holocaust and genocide and the issue of racism can’t come up. Inevitably, it’s going to.”

In her talks, Preston first paints a picture of a happy, privileged life in early childhood, then, little by little, unspools how she, as a Jewish child in Nazi-occupied Hungary, lost every right she had — and nearly her life. It’s a real-life lesson on racism — the Nazis considered Jews a race — against one group of people.

In 1944, when Hungary fell under German occupation, Preston was weeks away from turning 5. Preston’s father ran a wholesale fish business and often brought a fresh carp home for dinner, putting it in the bathtub to keep it cool. The young Preston would visit the fish there, she remembers. “I would say, ‘Look, I’m so sorry we’re going to eat you, but you’re going to taste so good,’ ” she told the Kingswood students, sparking laughter. Preston recalls, too, the joy of regular visits by her father’s relatives. “I basked in this wonderful love of all of these people.”

Change happened gradually at first. The Nazis began prohibiting Jews from going to school or work, and then other places. “There was a special bench with a yellow stripe on it, and it said ‘Jew,’ ” she tells students. “I could no longer go to the swimming pool with my daddy because that would be ‘contaminated’ by us.”

Roundups of Jews began, and her father and all of his relatives were taken to a fenced-in ghetto. Preston was supposed to go, too. At first, her mother hid her at home. Then a dairy farmer, grateful to Preston’s mother for making her wedding dress, offered to hide the girl in her barn, taking her there in a farm cart. One day, soldiers came and Preston heard them say to her rescuer, “Where’s the Jew? We have information you’re hiding a Jew.”

“I open my eye and a big black boot is right next to my head, and then a bayonet comes down an inch away from my head and gets stuck in the wood next to my face. Then he pulls it out and they leave. That’s somehow when my real childhood ended.”

Kati Preston, Holocaust survivor who advocated for New Hampshire’s Holocaust education law

After searching the house, the soldiers headed to the barn and climbed up to where Preston had buried herself under hay. “I open my eye and a big black boot is right next to my head, and then a bayonet comes down an inch away from my head and gets stuck in the wood next to my face. Then he pulls it out and they leave,” she recalls. “That’s somehow when my real childhood ended.” She stayed in the barn for three months until the war was over.

Preston and her mother learned the details of what had happened to her father from the man at the train station. After her father and another prisoner at Auschwitz stole a piece of bread, both were stripped of their clothes, beaten, put in a dog kennel, and left in a field.

“It took my father two days and a night to die,” Preston told the students, as one girl covered her face in horror.

That man from the station went on to marry Preston’s mother. A few years later, he told Preston how at Auschwitz, the Nazis had made him go in one group and his first wife and their daughter, 11-year-old Dita, were directed to another — the group that was sent immediately to be killed in the gas chambers. At her school presentation, Preston raised high a photo of Dita, a girl with long braids. “She was only a few years older than me, and this little girl was killed only because she was a Jew.”

The day after Preston’s talk at Kingswood High, Kelliher led a discussion about it in class. The 14 juniors and seniors sat in a circle as their teacher turned down the lights and said quietly, “Let your eyelids be soft on your eye- balls. Take a breath.” Moments later, she tapped a chime, then asked for their impressions of Preston’s presentation.

One thing really stuck with Tegan Perkins-Levasseur, he told his classmates: It took Preston 50 years to stop feeling her own sense of hate. “I have four sons,” Preston had recollected, “and every time I gave birth to one of my sons, I was giving the finger to Hitler.” Perkins-Levasseur added, “It really made me think she has such strength.”

Next, the teacher asked, “What contributes to people becoming the evil that Nazis were?”

Austin Johnson, a senior, said Hitler came to power at a time of economic woes for Germany. “When you have a leader that comes in and says, ‘Everything will be great,’ says, ‘We’re going to make this place great,’ you can get an entire country to do what he wants,” he said. Another student, Gabe Hibbard, offered, “One of the factors was really the propaganda and teaching the Nazis that ‘hey, it’s OK to bully Jews.’ ”

Kelliher nodded, and then she asked, “Are there parallels to this in the world today?”

This is as close as Kelliher would get in class to connecting the Holocaust to today. She offered no answers to her question, and students did not latch onto it. Kelliher moved on.

“It really has had a chilling effect on teachers new to the classroom, especially teachers who may not have knowledge on teaching about genocide. What has happened is teachers are saying they’re not going to teach it at all.”

Evan Czyzowski, a Bedford, New Hampshire, high school teacher

After class, Kelliher said the divisive concepts measure was on her mind as she taught. “It’s just a little more pressure on the words I choose.” Rather than risk a parental complaint, she puts the burden on students to bring up concepts such as systemic racism. She resents the threat hanging over her while she teaches. “It’s the stress of having to manage all of this and making sure that you’re educating them in a way that they need to be educated about these topics.”

Unlike Kelliher and some of her other colleagues, one Kingswood social studies teacher I interviewed supported the divisive concepts law and said it did not affect his teaching. He did not want his name used, partly because his view of the law is unpopular, particularly among other educators. Teachers should “stick to the facts” and help students develop the skills to reach their own conclusions, he said. “I think the kids are sophisticated enough to make the connections.”

Nicholas Germana, the German history professor and state legislator, disagrees that students will make the connections. Without teachers to help connect the dots between the past and today, he fears students will make incorrect inferences, or draw no conclusions at all, he says. And yet helping them make such connections is “exactly the kind of thing you could lose your teacher’s license over.”

Elements of totalitarianism are not new in the United States, says Germana, noting that in the 1930s, the German American Bund organization, a U.S. group supporting the Nazis, held a rally at Madison Square Garden with a picture of George Washington and the Nazi swastika on display. The America First movement was founded in 1940.

“[The America First movement] is associated with things Trump talked about when he be- came president . . . the Muslim ban, the birther lie about President Obama, and the cozying up to strongmen like [Russian President Vladimir] Putin,” Germana says. “You put yourselves in a dangerous situation of thinking those forces are still not present in your society.”

The Proud Boys, a far-right group with leaders among those convicted of plotting the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, is one such example, Germana says. “You can compare Proud Boys to the creation of terrorist political cells in Germany. When you see the normalization of violence [today], the parallel between now and the 1920s is frightening.”

At a January 20 training on Zoom for about 24 teachers from around New Hampshire, Tom White of Keene State tried to reassure teachers that New Hampshire’s Holocaust education requirements permitted them to talk about political oppression, bigotry, and implicit bias, despite their fears. “What I’m trying to argue today is you are safe in dealing with difficult topics,” he said, though he went on to add that it didn’t mean pressure will not come from particular groups that traffic in fear and intimidation.

He played a video clip of a teacher in Germany talking about her country’s commitment to teaching schoolchildren about the Holocaust to prevent genocide from repeating. “I also want Americans to think about what they would say if Germany all of a sudden decided ‘OK, we’re no longer teaching [about] Nazi Germany in schools because it’s too difficult for children to learn about that at age 10,’ ” she said in the video. But learning at age 10 that her grandparents’ generation and people she’d known or loved had helped perpetrate the Holocaust did not traumatize her, she continued. Instead, it made her a more politically aware, informed citizen.

Despite White’s reassurance, some teachers at the workshop said they remain afraid and struggle with how to have difficult conversations with students. One teacher spoke of an administrator accusing her of promoting a liberal agenda; others said their administrators had given little or no guidance on how to deal with the divisive concepts law and its fallout. “It really has had a chilling effect on teachers new to the classroom, especially teachers who may not have knowledge on teaching about genocide,” said Evan Czyzowski, a Bedford, New Hampshire, high school teacher who co-taught the workshop with White. “What has happened is teachers are saying they’re not going to teach it at all.”

“If we’re learning about the Holocaust but not thinking about how that should inform our future decision making, what’s the point of learning about it? If it’s something bound in the past that has no relevance to today, I think we’re missing the point.”

Sean O’Mara, a social studies teacher at Keene Middle School

At the workshop, Morgan Baker, a teacher at Conant Middle High School in Jaffrey, sought advice from White. “You used the phrase ‘systemic racism.’ If I’m being honest with you, that’s not a phrase I’m comfortable using in my classroom,” said Baker, who said students have come into his classes carrying Confederate flags or displaying it on T-shirts or hats. “I’m a new teacher . . . It’s a lot to wrap my head around. How do I do this without dealing with a lot of backlash?”

In his answer, White shared an anecdote about a ninth-grade student who shouted “Proud Boys Rule!” in the middle of a lecture on the Holocaust at a New Hampshire high school. When White asked the student why he felt that way, the student explained why he thought the Proud Boys were important and that he disliked Biden, alleging that the president was a pedophile.

Eventually, White recognized that the student had misinterpreted a photograph — popular in online conspiracy theorist circles — of Biden comforting his granddaughter at her father’s funeral. When White explained the picture, the boy was taken aback and pledged to remove his social media posts spreading the misinformation. White advised Baker to start a similar conversation with students displaying the Confederate flag.

After the workshop, Baker and his colleague Susan Graage, who teaches about the Holocaust in literature classes, tell me they appreciate White’s advice but remain worried. Some students will just blurt out “Hitler” and laugh, Graage says. “I feel like that didn’t happen 10 years ago.”

Teaching about racism in general is the main target of divisive concept laws, and the law has hurt attempts to teach about hate in all of its forms, New Hampshire teachers told me in interviews. An English teacher at Kingswood, Sarah Straz, says some community members’ right to know requests searching for references to diversity and related topics have instilled fear in some teachers. And yet, she says, in a predominantly white school like hers, it should be an imperative to make sure the students know about the historical oppression of African Americans and how it relates to today.

At least six other states have both Holocaust education mandates and divisive concepts laws, according to Jennifer Goss, program manager of Echoes & Reflections. Despite assurances to the contrary, she believes the laws, in addition to negatively affecting instruction on Black history, are leading to restrictions on Holocaust education. Several schools around the country, for example, have pulled a graphic adaptation of Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” because of her ponderings about human sexuality and kissing a female friend, which critics describe as promoting a homosexual agenda. In Colorado, a state board member tried to remove the word “Nazi” from standards on Holocaust education to, as Goss says, “deemphasize the role of a nationalistic political party in the Holocaust.”

White himself has experienced resistance to language he has used. In April, after he spoke to the roughly 200 eighth graders at Keene Middle School, a parent complained to the principal that White referred to the Nazis as a right-wing movement and compared them with today’s Republican Party in America. The parent did not attend the talk and was basing the complaint on what their child had relayed. White says he didn’t make a comparison to the GOP, but that he had referred to the Nazi party as right wing because that’s a historical fact.

Sean O’Mara, a social studies teacher at Keene Middle School who attended that talk, frets about the current atmosphere’s effect on teaching history. “If we’re learning about the Holocaust but not thinking about how that should inform our future decision making, what’s the point of learning about it?” he asks. “If it’s something bound in the past that has no relevance to today, I think we’re missing the point.”

Kati Preston plans to speak at schools for as long as she’s able. She’s troubled when she hears about book banning, a hallmark of the Nazi regime. “It worries me because I see parallels,” she says. Still, the students she meets give her hope. Inevitably, moved by her words, some stand in line to meet her and exchange hugs. Some write letters: An eighth grader recently wrote her to say he was ashamed by some of his behavior and that her speech made him want to be a better person.

Some students, such as Tegan Perkins-Levasseur at Kingswood, seek her wisdom in the question-and-answer period after her talks. “What’s one thing you would tell the younger generation today about what happened back then?” he asked her at Kingswood High.

“I think I would tell them to get an education. The more you know, the less you fear. The less you fear, the less you’re violent,” Preston responded. “Most things happen because you’re afraid of the ‘other.’ I think education makes us more equal.”

*Clarification: This story has updated to clarify that a bill to mandate Holocaust education has been introduced in Vermont.

This story on learning about the Holocaust was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education, in partnership with The Boston Globe Magazine. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

I love this article , thank you

What happens when one or two students go home, crestfallen, and ask Mom or Dad, “Did your grandfather back in Germany murder Jews?” When the students profess shame as having ancestors who lived in Germany in the 30s and 40s?