OWENTON, Ky. — During a school-wide club fair in this northern Kentucky town, a school administrator stood watch as students signed up for a group for LGBTQ+ students and their allies.

After the club sign-up sheet had been posted, students wrote derogatory terms and mockingly signed up classmates, according to one of the club’s founders. The group eventually went to the administrator, who agreed to help.

Simply being able to post the sign-up sheet in school was a victory of sorts. For two years, the club, known as PRISM (People Respecting Individuality and Sexuality Meeting), gathered in the town’s public library, because its dozen members couldn’t find a faculty adviser to sponsor it. In fall 2022, after two teachers finally signed on, the group received permission to start the club on campus.

Much of that happened because of one parent, Rachelle Ketron. Ketron’s daughter Meryl Ketron, who was trans and an outspoken member of the LGBTQ+ community in her small town, had talked about wanting to start a Gay-Straight Alliance when she got to high school. But in April 2020, during her freshman year, Meryl died by suicide after facing years of harassment over her identity.

Following Meryl’s death, Ketron decided to continue her daughter’s advocacy. She gathered Meryl’s friends and talked about what it might mean to start a Gay-Straight Alliance, a student-run group that could serve as a safe space for queer youth on campus. After trying, and failing, to get the school to sign off on the idea, the group decided to gather monthly at the public library, where its members discussed mental health, sex education and experiences of being queer in rural areas. Ketron, a coordinator of development at a community mental health center just across the border in Indiana, also founded doit4Meryl, a nonprofit that advocates for mental health education and suicide prevention, specifically for LGBTQ+ youth in rural communities like hers.

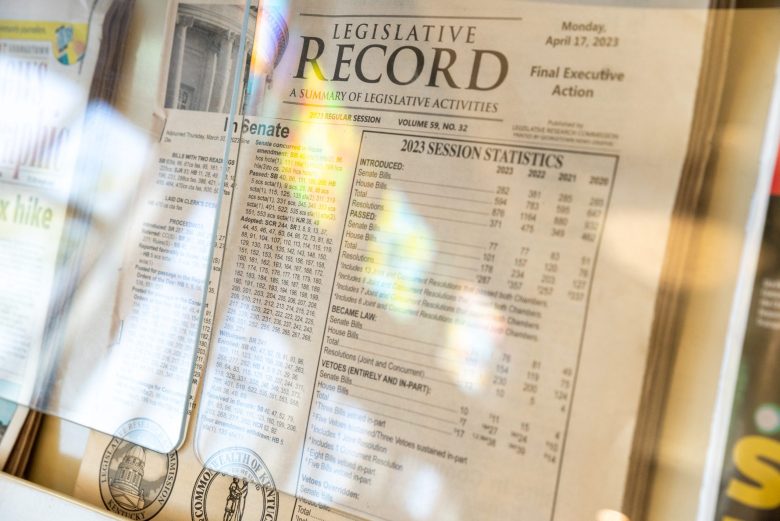

Around the country, LGBTQ+ students and the campus groups founded to support them have become a growing target in the culture wars. In 2023 alone, 542 anti-LGBTQ+ bills have been introduced by state legislatures or in Congress, according to an LGBTQ-legislation tracker, with many of them focused on young people. Supporters of the bills say schools inappropriately expose students to discussions about gender identity and sexuality, and parents deserve greater control over what their kids are taught. Critics say the laws are endangering already vulnerable students.

Kentucky’s law, passed in March, is one of the nation’s most sweeping anti-LGBTQ+ laws, prohibiting school districts from compelling teachers to address trans students by their pronouns and banning transgender students from using school bathrooms or changing rooms that match their gender identity. The law also limits instruction on and discussion of human sexuality and gender identity in schools. A separate section of the law bans gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth in the state.

“What started out as really a bill focused on pronouns and bathroom use morphed into this very broad anti-LGBTQIA+ piece of legislation that outlawed discussions of gender and sexuality, through all grades, and all subject matters,” said Jason Glass, the former Kentucky commissioner of education. Glass left the state in September to take a job in higher education in Michigan after his support for LGBTQ+ students drew fire from Republican politicians in Kentucky, including some who called for his ouster.

Related: In the wake of ‘Don’t Say Gay,’ LGBTQ students won’t be silenced

Because the law’s language is sometimes ambiguous, it’s up to individual districts to interpret it, Glass said. Some have adopted more restrictive policies that advocates say risk forcing GSAs, also known as Gender and Sexuality Alliances or Gay-Straight Alliances, to change their names or shut down, and led to book bans and the cancellation of lessons over concerns that they discuss gender or sexuality. Others have interpreted the law more liberally and continue to offer services and accommodations to transgender or nonbinary students, if parents approve.

Across the country, the number of GSAs is at a 20-year low, according to GLSEN, an LGBTQ+ education advocacy nonprofit. GLSEN researchers say there may be two somewhat contradictory forces at work. Fewer students may feel the need for such clubs, thanks to school curricula and textbooks that have become more inclusive of LGBTQ+ individuals and thanks to an increase in the number of school policies that explicitly prohibit anti-gay bullying. Conversely, the recent surge in anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, as well as the halt to extracurricular activities during the pandemic, may also be fueling the drop, the researchers said.

Willie Carver, a former high school teacher and Kentucky’s Teacher of the Year in 2022, left teaching this year because of threats he faced as an openly gay man. Laws like the one in Kentucky legitimize and legalize harassment against LGBTQ+ kids, he said, and may even encourage it. “We’ve ripped all of the school support away from the students, so they’re consistently miserable and hopeless,” he said.

Owenton is a picturesque farming community with rolling green hills and winding roads located halfway between Cincinnati and Louisville. Its population of about 1,682 is predominantly white and politically conservative: The surrounding county has voted overwhelmingly Republican in every presidential election since 2000.

Ketron moved here from Cincinnati in 2014 with her then-husband, seeking to live on a farm within driving distance of large cities. Shortly after the move, she recalled, a city official visited the property to give Ketron a rundown of expectations in the community — and a warning.

“It was basically ‘You better watch what you do and don’t get on the bad side of people because one person might be the only person that does that job in this whole county.’ Do you understand what I mean?’ ‘Yup,’” Ketron recalled saying, “‘I understand what you mean.’”

A few years later, she met her now-wife, Marsha Newell, and the two began raising their blended family of eight children on the farm. They also started fostering LGBTQ+ kids. Ketron said her family is one the few in the county to accept queer kids. Their children were often met with hostility, Ketron said; other students made fun of them for having two moms and told them that Ketron and her wife were sinners who were “going to hell.”

Ketron said the couple thought about moving, but beyond the financial and logistical obstacles, she worried about abandoning LGBTQ+ young people in the town. “Just because I’m uncomfortable or this is a foreign place for a queer kid to be doesn’t mean there aren’t queer kids born here every day,” she said.

Related: Inside Florida’s ‘underground lab’ for far-right education policies

After Meryl came out to family and friends in fifth grade, the bullying at school intensified, Ketron and Gwenn, Meryl’s younger sister, recalled. Few adults in Meryl’s schools took action to stop it, they said. When Meryl complained, school staff didn’t take her seriously and told her to “toughen up and move on,” Ketron said. (In an email, the high school’s new principal, Renee Boots, wrote that administrators did not receive reports of bullying from Meryl. Ketron said by the time Meryl reached high school, she’d given up on reporting such incidents.)

That said, as she got older, Meryl became more outspoken. As a ninth grader, in 2019, she clashed with students who wanted to fly the Confederate flag at school; Meryl and her friends wanted to fly a rainbow flag. The school decided to ban both flags, Ketron said. After that, Meryl brought small rainbow flags and placed them around campus. (According to Boots, students were wearing various flags as “capes” and were advised not to do so as it was against school dress code.)

Ketron said she generally supported her daughter’s advocacy, but sometimes wished she’d take a less combative approach. “You might need to dial it back a little bit,” Ketron recalled telling Meryl once, when her daughter was in eighth grade.

Ketron recalled seeing Meryl’s disappointment; she said it was the only time she felt that she let her daughter down.

For years, the most effective wedge issue between conservatives and progressives was marriage equality. But when the Supreme Court in 2015 recognized the legal right of same-sex couples to marry, opponents of gay rights pivoted to focus on trans individuals, particularly trans youth. After early success with legislation banning trans kids from playing sports, conservative legislators began to expand their efforts to other school policies pertaining to LGBTQ+ youth.

The ripple effects of these laws on young people are becoming more apparent, said Michael Rady, senior education programs manager for GLSEN. Forty-one percent of LGBTQ youth have seriously considered suicide in the past year, according to a 2023 survey by The Trevor Project, an LGBTQ+ suicide prevention nonprofit. Nearly 2 in 3 LGBTQ+ youth said that learning about potential legislation banning discussions of LGBTQ+ people in schools negatively affected their mental health.

Konrad Bresin, an assistant professor in the department of psychology and brain sciences at the University of Louisville whose research focuses on LGBTQ+ mental health, said that for LGBTQ+ individuals just seeing advertising that promotes legislation against them has negative effects. “Even if something doesn’t pass, but there’s a big public debate about it, that is kind of increasing the day-to-day stress that people are experiencing,” he said.

Bresin said that student participation in GSAs can help blunt the effect of anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, since the clubs provide students a sense of belonging.

Supporters of Kentucky’s new law argue that the legislation creates necessary guardrails to protect students. Martin Cothran, spokesperson for The Family Foundation, the Kentucky-based conservative policy organization that advocated for the legislation, said the law is designed to keep students from being exposed to “gender ideology.”

Cothran said that nothing in the law impedes student speech, nor does it entirely prohibit traditional sex education. “It just says that you can’t indoctrinate,” he said. “Schools are for learning, not indoctrination.”

Related: College wars on campus start to affect students’ choices of college

When the law, known as SB 150, went into effect last spring, Glass, the former education commissioner, said school districts were forced to scramble to update their curricula to comply with the bill’s restrictions. In some cases, that meant removing any information on sexuality or sexual maturation from elementary school health curricula, and also revising health, psychology and certain A.P. courses in middle school and high school, he said.

Some families have sued. In September, four Lexington families with trans or nonbinary kids filed a lawsuit against the Fayette County Board of Education and the state’s Republican attorney general, Daniel Cameron, alleging that SB 150’s education provisions violate students’ educational, privacy and free speech rights under state and federal law. The families say that since the law passed, their kids have been intentionally misgendered or outed, barred access to bathrooms that match their gender identity and had their privacy disregarded when school staff accessed their birth certificates in order to enforce the law’s provisions.

School districts that don’t comply fully with the law could face discipline from the state’s attorney general, said Chris Hartman, executive director of the Fairness Campaign, a Kentucky-based LGBTQ+ advocacy group.

“Teachers who before this were willing to speak out and advocate are, as a general rule, unwilling to speak publicly about what’s happening.”

Willie Carver, Kentucky Teacher of the Year, 2022

Meanwhile, LGBTQ+ and student rights advocates fear that GSAs in the state will close or change their names because of the law. Teachers from across the state have also shared stories about their schools removing pride flags and safe space stickers, banning educators from using trans students’ pronouns and names, and removing access to bathrooms for trans kids, according to Carver, the former Teacher of the Year, who is collecting that information as part of his work with the nonprofit Campaign for Our Shared Future. The law’s broad language has not only affected teaching about gender and sexuality, he said: Educators have complained of schools banning references to the Holocaust in image or film, removing books with LGBTQ+ characters, and nixing discussion of scenes in Shakespeare’s plays because of images that may depict nudity, sex or language that talks about sexuality and gender.

Educators and school staff are fearful, said Carver. “It’s nearly impossible to know what’s happening because the law gets to be interpreted at the local level. So, the district itself gets to decide what the law’s interpretation will look like,” he said. “And teachers who before this were willing to speak out and advocate are, as a general rule, unwilling to speak publicly about what’s happening.”

For supporters of the law, that may be the point. GLSEN’s Rady said the bills are often written in intentionally vague ways to intimidate educators and school district leaders into removing any content that might land them in trouble. This year, his group is focused on providing educators, students and families information about their rights to free speech and expression in schools, including their right to run GSAs, Rady said.

In March 2020, when the pandemic hit and schools went remote, Meryl, then a high school freshman, posted a video diary on social media. In it, she strums her ukulele, and shares a message to her friends. “Some of you guys don’t have social media, some of you guys don’t like being at home,” Meryl said in the video. “I won’t get to see you guys for a whole month which is awful because you guys make me have a 10 times better life, you guys make mountains feel like literally bumps and steep cliffs just feel like a little bit of walking down the stairs.”

The video ends with her saying she’ll see her peers in school on April 30, when schools were scheduled to reopen. On the morning of April 18, Meryl died.

Ketron, Meryl’s mother, had thought remote school would be a relief for her daughter after years of bullying in school buildings. But it was difficult to be separated from her friends, she said, and Meryl also knew some of them were struggling in homes where they did not feel accepted.

“Suicide is never one thing,” Ketron said. “A lot of times people talk about death by a thousand paper cuts. As sad as it sounds, for me to have that come out of my mouth, I feel like that really speaks to Meryl’s life. She had wonderful things, but it was just like thousands of paper cuts.”

For months after Meryl’s death, Ketron would read text messages on Meryl’s phone from her friends sharing stories about how she’d stood up for them in school and in the community. Ketron said she made a promise to herself — and to Meryl — that she was going to be loud like her daughter and “make it better.” In the spring of 2020, she started doit4Meryl.

“I don’t ever want this to happen again, ever, to anyone,” she said. “I never want someone to be in that place and pieces of it that got them there was hate and ignorance from another human being.”

In 2021, the anti-LGBTQ+ and anti-critical race theory book bans movement reached the Owenton community after a teacher in the district taught “The 57 Bus,” a nonfiction book that features a vocabulary guide explaining gender identities and characters who are LGBTQ+.

The book created an uproar in the town, with parents calling for its removal and for the educator to be disciplined. After that, Ketron said the few teachers who had seemed open to sponsoring the GSA no longer felt comfortable.

Related: Teachers, deputized to fight the culture wars, are often reluctant to serve

In mid-2021, Ketron decided to start the club herself, at the public library. Each month, a dozen or so kids gathered in one of the building’s study rooms, talking about what it means to be queer in rural Kentucky, and what they hoped to accomplish through their GSA. Some of them were Meryl’s friends, others were new to Ketron.

In July 2022, the group held a Color Run, a 5K to bring together various advocacy groups from around the county and state to uplift people after the isolation of Covid. Later that year, they invited Carver to speak about his experiences as an openly gay man growing up in rural Kentucky. The students worked with Ketron and doit4Meryl to create a “Be Kind” campaign: They printed signs with phrases like “You’re never alone” and “Don’t give up,” along with information on mental health resources, and placed them in yards around town.

In the fall of 2022, after two teachers agreed to serve as advisors for the GSA, the school principal allowed the club on campus. While Ketron checks in with the students occasionally, the club is now student-led, she said. The past school year would have been Meryl’s senior year, and the club’s students were excited about finally being welcomed onto campus, Ketron said.

Then Kentucky’s 2023 legislative session began with the onslaught of bills targeting LGBTQ+ youth that eventually merged to become SB 150.

Around the same time, tragedy entered Ketron’s life again: She lost one of her foster children, who was trans, to suicide. The loss of her daughters prompted her to spend countless hours in the state capitol, attending committee meetings and hearings and signing up to testify against the anti-trans and anti-LGBTQ+ bills on the senate floor. She watched, devastated, as legislators quickly voted on and passed SB 150.

“All I could think about was Meryl,” she said. “They’re just starting and this world is supposed to love them through this hard part. When you’re shaping yourself and instead we’re going to tell you that we don’t want you to exist.”

In Owenton, the district follows SB 150 as per law, said Reggie Taylor, superintendent of Owen County Schools. Little has changed as a result of the legislation, he said: “It’s been business as usual.” Trans and nonbinary students have long had a separate bathroom they could use and that hasn’t changed, he said, and the district offers a tip line for students to anonymously report bullying, as well as access to school counselors.

Ketron, though, sees fallout. Fearful of bullying and other harms, she said that she and the other parents with trans kids in the school system are trying to get their children support by applying for help through Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. While 504 plans are typically for students with disabilities, they are sometimes used to help secure LGBTQ+ students services and accommodations, such as protection from bullying, mental health counseling and access to bathrooms that match their gender identity.

SB 150 has also had a chilling effect on the work of the school’s GSA, according to Ketron. During the summer, after the law went into effect, PRISM members discussed changing the club’s name and direction to focus on mental health.

Related: How do we teach Black history in polarized times?

Across the state, students and educators are grappling with what their schools will look like as the law takes hold. In March, Anna, a trans nonbinary student from Lexington, launched an Instagram account called TransKY Storytelling Project, anonymously documenting the impact of the new law on young people and teachers.

People shared examples of the ways the legislation affects them, such as making them afraid to go to school, erasing their identities and making the jobs of educators and librarians tougher. A middle school guidance counselor in rural Kentucky wrote that the new law makes it harder to connect with students and support them: “If we are the only ones students have, and we can’t provide them the care they desperately need and deserve, the future looks very bleak.”

Even in the state’s more progressive cities, the law has changed daily life in schools, Anna, the Instagram account’s curator said. The GSA at Anna’s Lexington high school used to announce club meetings and events on the loudspeakers and post flyers in school hallways, Anna said. But the group has since gone underground, to avoid bringing attention to its existence lest administrators force it to stop meeting.

“The school felt so much safer knowing that [a GSA] existed because there were students like you elsewhere. You could go in and say, ‘Hey, I’m trying out this set of pronouns. I’m trying to learn more about myself. Can you all like call me this for a couple of weeks?’” Anna said. “It just allowed for a place where students like me could go.”

But while the absence of a GSA is concerning, Anna fears most the impact of SB 150 on students in rural parts of Kentucky. GSA members from rural communities have shared that they no longer have supportive school staff to advocate for their clubs because of the climate of fear created by the law, Anna said.

That said, November’s election brought some hope for LGBTQ+ advocates: Cameron, the state attorney general who backed SB 150 and campaigned on anti-trans policies, lost his bid for the governorship to incumbent Andy Beshear, and several other candidates for office who advocated anti-trans policies were defeated too.

Back in Owenton, Ketron is working with Carver to plan a summit for Kentucky’s rural, queer youth. Ketron said she hopes the gathering will serve as a reminder for students that even though they may be isolated in their communities, there are people like them across the state.

But as of this fall, participating in a GSA is no longer an option for students at the Owenton high school. Boots, the school principal, wrote in an email that the club had changed its focus, to one geared toward addressing “social needs across a variety of settings.”

But according to Ketron, students said they were afraid to continue a club focused on LGBTQ+ issues in part because of SB 150. She offered to help students restart the club in the library, or at her house, she said, but members worried that would be too difficult because many of them have not come out to their families.

Ketron said she’s not giving up. “At its core,” she said, a GSA is “a protective factor and so very needed, especially in a rural community.”

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org for free, 24-hour services that can provide support, information and resources.

This story about LGBTQ+ students in schools was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter, and share your thoughts about this story at editor@hechingerreport.org.