This story is part of a series about how schools, teachers and students are coping with the immigration crisis.

SANTA FE, N.M. — Albuquerque teacher Juan Ortega saw a change in one of his fourth graders after the boy came home from school one day to find his father had been deported. The student was one of Ortega’s strongest in the high-achieving bilingual program at Armijo Elementary, located in an area often patrolled by Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“He plummeted,” Ortega said. “He plummeted for a while until we were able to try to get him to understand that we use every obstacle as an opportunity. That’s always been my motto with my kids.”

Ortega had a conversation with the 9-year-old boy “about how his parents had sacrificed everything to give him an opportunity to become someone successful.” Ortegas’s eyes mist as he recounts the story. “Because you care, a great deal, for them. So what happens to them, happens to you in a way.”

While U.S. military troops have been at the border with Mexico since last fall as part of the Trump administration’s efforts to deal with an influx of asylum seekers, teachers in the classroom have been on the front lines of immigration enforcement for decades, doing their best to support students whose family members have been deported or who face deportation themselves. Ortega first taught students affected by immigration policy during the Obama administration, which deported nearly 5.3 million people.

A 1982 Supreme Court decision affirmed the right of all children to receive a free public education, and schools are not allowed to ask about a student’s immigration status. Still, teachers see firsthand the fear and fallout of policy swings — including President Donald Trump’s decision to deport “all removable aliens.”

Ever since President Donald Trump’s election, teachers around the country — especially at schools with a high percentage of students of color — say they’ve noticed a surge of anxiety among students from immigrant families vulnerable to deportation.

What happens if an ICE agent walks in the door of our school? Prior to this training, I would have had no clue.

Teachers’ jobs have been complicated by rising absenteeism, frustrated undocumented high schoolers who face insurmountable obstacles to attending college, and overstretched students who have taken on a job to help the family after a parent has been deported. And teachers themselves worry about what to do if Immigration and Customs Enforcement comes knocking.

Feeling a moral and ethical duty to help — yet uncertain how far their legal rights allow them to go — teachers are turning to nonprofit immigration law offices, training by education experts, and their own initiative to educate themselves.

Related: The unseen obstacles facing undocumented college students

“Students, teachers and administrators have rights, and have rights to protect the people around them, including their own students,” said Rebekah Wolf, an immigration lawyer with the nonprofit New Mexico Immigrant Law Center.

In the months after Trump’s inauguration, Wolf, a former high school teacher, initiated “know your rights” training sessions for educators in Santa Fe and Albuquerque. She focused her training on “what ICE is supposed to do and what ICE isn’t supposed to do.”

People rarely think about what it’s like to assert their right to free speech “right there in flesh and blood” when encountering an ICE agent in person, Wolf said. They often don’t realize — or remember in the heat of the moment — that “ICE operates on consent and they’re allowed to ask, but people can say no.”

“What we train teachers to say is, ‘I’m not answering your questions,’” Wolf said. But if they do start answering questions, she added, it’s illegal to lie to a law enforcement officer.

Schools are among the “sensitive locations” where ICE is supposed to refrain from conducting raids, as stated in an Obama-era policy still in place. Overall, the annual number of deportations has been lower under Trump than under President Barack Obama, although it rose by 13 percent last year to about 256,000 people. Since Trump issued an executive order during his first week in office expanding the scope of immigration enforcement, there’s been a sharp increase in the removals of immigrants without criminal convictions.

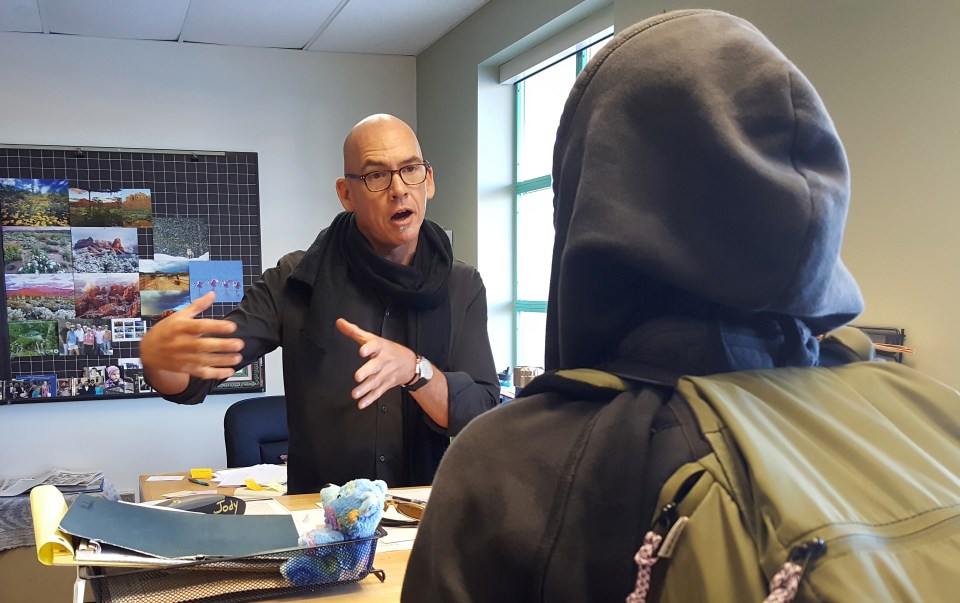

High school teacher Jody LeFevers jumped at the chance to attend one of Wolf’s training sessions. Over the years, a handful of his students at The MASTERS Program, a charter school housed at Santa Fe Community College, have confided their immigration problems to him.

“What happens if an ICE agent walks in the door of our school? Prior to this training, I would have had no clue,” LeFevers said. “The training forced our institution to have a conversation, both on a legal level and on a moral level.” He thinks it’s the school’s responsibility to be prepared for any scenario, but said “at some point it comes down to each individual” to determine their own moral obligation to protect students.

Wolf said teachers often ask the same questions. They want to know if they’re legally required to tell an ICE agent if a child is in school. If they decline to answer, are they interfering with an investigation? Do school employees have to comply if an agent asks them to search the school database for information such as which students do not have social security numbers?

The answer to all those questions is no, Wolf said, unless a law enforcement agent presents a warrant signed by a judge.

In Santa Fe, a sanctuary city, an ordinance prohibits city employees, including public school district staff, from turning over information to ICE without a judicial warrant.

Wolf tells teachers it’s legal to take pictures of ICE agents and to talk about their presence, but “putting a student in your car for the purposes of evading a particular enforcement activity” is not. And standing in the classroom doorway and refusing to let an ICE agent in is “probably interfering with a federal enforcement officer,” she said. “It’s probably against the law, it’s probably a misdemeanor.”

On uncertain ground is whether it is legal to send out messages to the entire student body through the school’s text message alert system saying ICE is on campus. The law is not settled on that yet, she said. There is a free speech argument to be made, but “there is an argument that you’re interfering with their enforcement, which is against the law.”

Since taking Wolf’s class, LeFevers has shared the information he received, offering training to faculty at the beginning of the school year and holding training sessions for interested students and parents. He makes it known he is the school’s point person on immigration concerns and provides phone numbers for people to call if they are confronted by ICE agents.

Elementary and school-age children, regardless of their nation of origin or immigration status, have a right to a public education in the state in which they reside — a right recognized by the Supreme Court in 1982 in Plyler v Doe. The number of children affected is significant: 5.6 million children younger than 18 were living in the United States with their undocumented parents in 2016, according to the Pew Research Center. Of those children, 675,000 were undocumented immigrants and at risk of being deported themselves.

Trump’s heated campaign rhetoric about deporting millions and his rescission of DACA early in his administration unsettled many immigrant families. Right after he was elected, immigration lawyer Allegra Love’s phone started ringing. Love, a former teacher, received calls from teachers and principals who were asking, “What do we tell the kids?” Love’s pro bono work through her nonprofit, Santa Fe Dreamers Project, has earned her a national reputation and she heard from educators around the country.

Related: DACA students persevere, enrolling at, remaining in and graduating from college

In summer 2017, Love explored how to support immigrant students and their families at a week-long workshop in Santa Fe for 30 teachers from New Mexico and out of state.

She provides professional development sessions at schools by invitation, but said expectations are often unrealistic. In a 35-minute, once-a-year session, she “can’t scratch the surface.” She suggests school districts ramp up their efforts to connect teachers with information about how to support immigrant families by appointing school immigration liaisons who would meet once a month with experts to get updated and then report back to their schools. Love recommends that families vulnerable to deportation establish an action plan, much as they would for any other emergency.

Of the 5.6 million children younger than 18 living in the U.S. in 2016 with one or more undocumented parents, about 675,000 were unauthorized immigrants themselves.

In November, Love was invited to a school to answer fourth-graders’ questions about the family separations at the border that sparked a national outcry last summer. “When you’re 10, it’s just deep discomfort that you don’t have a name for. And that makes you feel confused and anxious,” she said. A visit last May to a fifth-grade class for career day ended abruptly when the conversation led to what kind of lawyer she was. When she mentioned immigration, “all hell broke loose,” she said. “Kids were crying, because there’s so much fear.”

The American Federation of Teachers, a labor union, also offers guidance for teachers. It has held community forums with special breakout sessions aimed at educators wanting to help students from undocumented immigrant families and contributed to a guide for educators published by the National Immigration Law Center.

Laura Guzmán-DuVernois, an Army veteran and educator fondly known as “Dr. D,” has become another resource for educators.

Years ago, when she was a teacher at an urban elementary school in Orlando, Florida, Guzmán-DuVernois’ interaction with a 10-year-old Honduran boy named Carlos became a catalyst for her decision to develop expertise in immigration policy and students’ rights. She later wrote a dissertation on the subject for her doctorate in education.

On his first day at the school, Carlos arrived to her reading class for Spanish speakers “all scratched up.” Concerned, she asked him what had happened, but he wouldn’t answer, so she reported it to the nurse. Weeks later, when he was comfortable with her and the class, she recalls, he said to her, “Missy, now I can tell you why I was scratched up. It’s because I was on ‘La Bestia.’”

Carlos described his journey from Honduras to Guatemala to Mexico, where he caught the train known as “The Beast.” His scratches came from the last leg of the journey, a walk through the spiny desert landscape of Arizona.

Guzmán-DuVernois googled “La Bestia.” “And then I became embedded into listening to their stories,” she said. “I would teach them vocabulary, but they taught me about the trials and tribulations they went through just to get to my classroom.”

Now, Guzmán-DuVernois has a full-time job as assistant principal of Silva Health Magnet High School, a three-time national Blue Ribbon school in El Paso, but travels to share her knowledge with groups like the Mexican American School Boards Association. At a dual-language conference last November in Santa Fe, she presented “The Impact of Immigration and Policy on Immigrant Students — The K-12 Perspective.” The room was packed to capacity with 40 educators from across the country.

Students, teachers and administrators have rights, and have rights to protect the people around them, including their own students.

Guzmán-DuVernois explained that Plyler v. Doe stemmed from a challenge to a 1975 Texas law that withheld education funding for undocumented students and allowed public school districts to deny their enrollment, leading one district to charge $1,000 annual tuition for any undocumented child who wished to attend.

She walked educators through a brief history of immigrant rights, including attempts in California and Alabama to circumvent the Plyler decision. She touched on DACA; the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, which makes special provisions for homeless students and is a useful tool for families of undocumented students who don’t have utility bills to prove residency; and other key laws and guidelines, including a May 8, 2014 “Dear Colleague Letter” from the departments of Justice and Education reminding school districts they must provide equal education to all children. The letter states districts cannot use acquired data on student race and ethnicity “to discriminate against students” nor can they deny a child’s enrollment if the parent refuses to provide the information.

Related: Immigrant students find hope in soccer, but some states won’t let them play

Juan Ortega, now teaching at Coronado Elementary School in Albuquerque, attended Guzmán-DuVernois’ session. Ortega said younger students will just come right out and say their mother or father is gone, whereas older students are developing filters and are less likely to say anything about their personal concerns regarding immigration enforcement. “They’ll share with you if they trust you,” he said.

Many educators worry the trust that is foundational to healthy school cultures has eroded in the last two years, and not just for immigrant families. A 2018 study by the UCLA Civil Rights Project on the effects of recent immigration enforcement on public school educators reported three key findings: educators are anxious and stressed, they’re overworked, and they trust their colleagues less.

Twenty-eight years into his teaching career, Jody LeFevers, of Santa Fe, tries to stay optimistic. He designs his courses to give his high school students the constitutional framework they would need to argue immigration policy with any expert, and the tools to “envision a better world… and square their shoulders to this world in a lot of ways, and be able to find a strong identity and something to believe in.”

“I don’t know if that’s possible,” he said, “but it keeps me coming in every day.”

This story about teachers and deportations was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.