This story is the first in a series about police officers in schools produced in a partnership between The Huffington Post and The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

TERRY, Miss. —Keyla Walker, a recent graduate of Terry High School, says she still remembers police yanking her off a school bus to arrest her four years ago, following a fight she says didn’t even involve her. She still does not totally understand why, but on a warm morning during her freshman year, she and her twin sisters — both juniors — were rounded up after one of the twins slapped another student during the ride to school. All three girls were ushered into the principal’s office. They eventually were shackled and transported to a juvenile jail, where they were locked up.

Walker, a former honor student, says she and her sisters were asked at the jail to remove their clothes and put on prison-issued underwear, orange outfits and white shoes. One of the girls, who was having her period, was told to remove her tampon and insert one issued by the county.

The sisters were released the same day they were arrested, and charges against two of the girls were dismissed. But the family says it waited over a year to find out what would happen to the charges against the sister involved in the altercation.

“It traumatized me a lot,” said Walker, who was treasurer of the student council at the time of her arrest. “It brought me down as a freshman and lowered my self-esteem.”

The arrests at Terry High School, in a suburban district on the outskirts of Jackson, Mississippi, are part of a growing trend across the U.S.

”Whenever a child does the littlest thing they are quick to throw the police on them.”

Terry High is the lively home of fall football games, student volunteers and an award-winning choir. But according to a group of parents, it has a more sinister side: school-based police officers are arresting a rising number of teenagers, most of whom are black. Student advocates and civil rights activists say the students deserve much lighter punishments.

There were six arrests at Terry High School during the 2013-14 school year. Two years ago, there were 20. By March of the 2015-16 school year, school officials had reported 27 arrests, more than four times the number they recorded during the entire 2013-14 school year. Most were for disorderly conduct.

Related: New rules for school employees who use force with students in Mississippi

Terry High School is far from unusual. In an era when educators are increasingly fearful of mass shootings, police officers in many schools are becoming the new disciplinarians, arresting students for incidents that once merited a call home or a visit to the principal’s office.

Since the 1990s, at least 11 states have enacted legislation that funnels state funds into school policing programs. Four states — Mississippi, Indiana, Florida and Pennsylvania — passed such legislation in 2013, in the months after the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut.

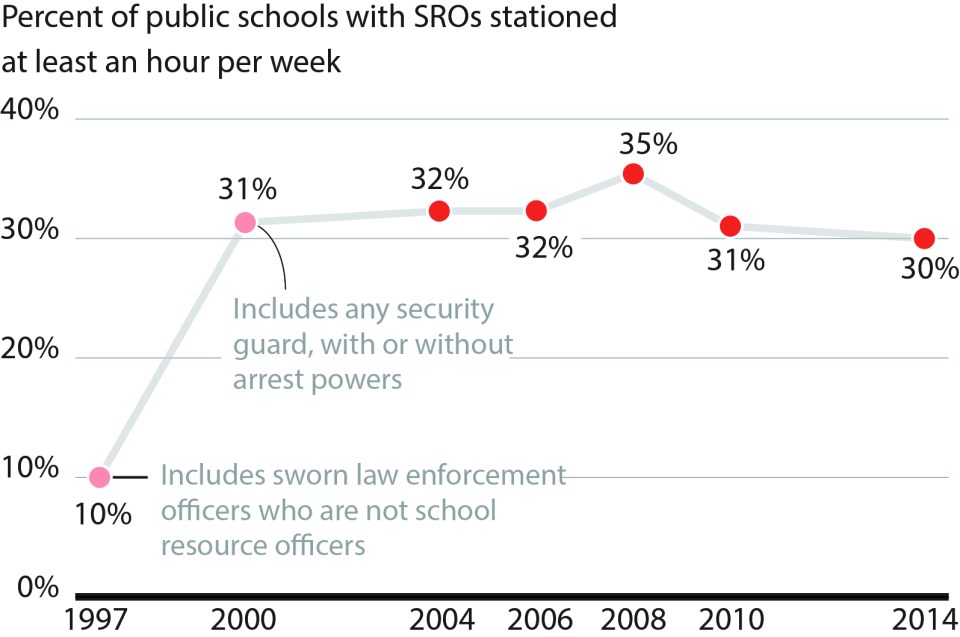

The combined result has been a dramatic increase in the number of schools with security officers. In 1997, the Department of Education reported that law enforcement officers were present in 10 percent of public schools at least once per week. By 2014, 30 percent of public schools had school resource officers, or SROs, the most common type of law enforcement on campuses.

Most of the money for police in schools comes from state and local funding streams. But federal funds doled out through the Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Services hiring program have also contributed. Established in 1994 by the Clinton administration, the program has so far given state and local law enforcement agencies $14 billion in grants — including over devoted exclusively to school resource officers, according to numbers The Huffington Post obtained from the Department of Justice.

In the 2014-15 school year, the number of student arrests at Terry High School was more than triple that of the year before, increasing from 6 to 20.

Studies examining whether schools become safer by having police officers on campus have produced conflicting results, according to a June 2013 Congressional Research Service report produced in response to Sandy Hook. Schools with sworn law enforcement officers were more likely to be patrolled, investigate student crime leads and possess emergency plans. But the research “does not address whether SRO programs deter school shootings, one of the key reasons for renewed congressional interest in these programs,” the report said.

And many parents, community members and civil rights activists say the presence of police officers inside classrooms does more harm than good. They complain that officers routinely punish children for small infractions and, in some cases, treat acts that parents categorize as “typical teenage behavior” like criminal activity.

Related: When fourth-grade problems include gunfire

Dennis Strong, the father of a Terry High junior who was handcuffed and transported to a local juvenile detention center after a cafeteria brawl last year, says he worries that administrators at the school are more predatory than protective.

“They don’t try to deal with anything,” Strong said. “They just call the police.”

Felisha Dixon, says her son, Janerio, now 18, stopped wanting to go to school last year, telling his mother he was afraid administrators were looking to apprehend him.

“Whenever a child does the littlest thing, they are quick to throw the police on them,” she said.

Indeed, a 2009 study published in the Journal of Criminal Justice showed that schools with school-based police officers have higher arrest rates for disorderly conduct than those without.

And a 2015 study using data from the National Center for Education Statistics showed that 61 percent of thefts at schools with police officers were referred to law enforcement, compared to 29 percent without. And 51 percent of vandalism incidents were referred to law enforcement at schools with officers, compared to 35 percent at those without.

The study concludes that officers inside schools have a significant impact on whether students interact with the criminal justice system, even after controlling for neighborhood crime and for state statutes that require schools to make certain arrests.

These arrests can have dire consequences, suggests a 2011 report by the Justice Policy Institute. Students who interact with the criminal justice system are more likely to drop out of high school, become involved with the system again and have higher unemployment rates than students who have not been arrested, according to the report.

Of further concern to critics is the disproportionate number of black students arrested. While black students represented 16 percent of the nation’s public school population in the 2011-12 school year, they made up 31 percent of students subjected to school-related arrests, according to a 2014 report by the U.S. Department of Education.

A similar disparity exists at Terry High School, where the population in the 2014-15 school year was 80 percent black, but 95 percent of the arrested students were black. The lone nonblack student arrested was Hispanic.

“Now in many schools, there is a presumption that it’s the kids that are somehow criminals. And race is playing a role.”

“What we’re seeing is mission creep,” said Dennis Parker, the director of the Racial Justice Program at the American Civil Liberties Union. “Now in many schools, there is a presumption that it’s the kids that are somehow criminals. And race is playing a role.”

Superintendent Delesicia Martin, who is black, said race does not play a role in student arrests within her district. Rather, she attributes arrests to students making “bad choices.”

“You can make good choices or you can make bad choices,” she said. “And they have to understand that if they make bad choices, there could be the possibility of a bad consequence going along with it.”

The fact that many armed officers are getting little to no training on in-school policing before entering schools also troubles student advocates.

As of last year, only a dozen states required police officers stationed in schools to undergo specific instruction related to their postings. And much of it is focused on crisis management, anti-bullying programs and shooter prevention, not on adolescent behavior — even though the National Association of School Resource Officers recommends officers receive 40 hours of basic training in a program it designed that includes lessons on the teen brain and conflict de-escalation techniques.

In Mississippi, the ACLU has lobbied the state legislature — so far unsuccessfully — to add 40 hours to its own training requirements and to add multiple job-specific lessons, including ones on adolescent development and local resources available to at-risk students.

If passed, the modified law also would have regulated when Mississippi officers need to complete their training. Currently, school-based officers can report to work before being fully trained.

Erik Fleming, director of advocacy and policy with the ACLU’s Mississippi chapter, says officers in schools need to learn how to de-escalate situations with the goal of avoiding arrests.

“The key is to keep a situation from getting to a felony situation,” he said.

Related: Will controversial new tests for teachers make the profession even more overwhelmingly white?

But proponents of in-school police officers, including Mississippi Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves, say officers serve as important crime-stoppers at a time when mass shootings are at an all-time high.

In Hinds County, Terry High School principal Roy Balentine knows what it’s like to be in a school under siege. In 1997, Balentine was principal at nearby Pearl High School when a young shooter killed two students and wounded seven others. He says officers make his school “safe and orderly.” Students are sufficiently warned about the consequences of behavioral infractions, like fighting. And he is certain those who commit those infractions “are dealt with appropriately.”

But parents whose children have been arrested say that punishment is unduly harsh for student misconduct because it stigmatizes kids, wreaks havoc on family lives and saddles parents with unwanted legal bills.

Students say being arrested has made them fearful of school, distrustful of authority figures and, in some cases, deeply angry.

Across the country, concern over the role police officers are playing in school discipline is mounting.

In 1997, law enforcement officers were present in 10 percent of public schools at least once per week. By 2014, the percentage with school resource officers — the most common type of law enforcement officer inside schools — was 30 percent.

The ACLU filed a federal lawsuit in Covington, Kentucky, last summer after a video of a school-based police officer shackling an 8-year-old boy with disabilities surfaced online.

And in October, the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of South Carolina began investigating the in-school arrest of a teenager who was violently thrown from a chair by an officer in Columbia.

Around that time, parents at Terry High School reached out to the state chapter of the Southern Poverty Law Center about their own concerns.

The group circulated a petition, calling for an end to “excessive and inappropriate” use of law enforcement. With dozens of signatures, it was presented to the county school board at a spring meeting. Protestors at the meeting wore T-shirts that read “Stop Arresting Our Students” on one side and “Let Kids Be Kids” on the other.

And in a letter this June, the Southern Poverty Law Center asked the district to modify its school district handbook, by removing all references to the Hinds County Juvenile Detention Center and including a stipulation that school officials reach out to parents before making arrests, among other requests.

Local lawyer Lisa Ross, whose clients include students who contend that they have been unfairly arrested, says she believes harsh discipline sends a worrisome message to students about their relationship to the criminal justice system.

“They are really preparing these kids for prison,” she said.

Not every parent is concerned about arrest rates at Terry High School.

David Johnson, the treasurer of the school’s Parent Teacher Organization, says he believes removing hostile students helps administrators maintain “a safe environment.”

And Pam Pilgrim, the mother of a junior at the school, says she is “comforted” by the presence of school-based police officers and “the actions they are taking.”

Keyla Walker, the recent Terry High School graduate who was arrested five years ago with her sisters after a school bus fight, disagrees.

Her mother, Stacy Walker, who had recently been diagnosed with colon cancer, says the incident was devastating for the entire family.

It frustrated and confused all three girls, but took an immense toll on the daughter who had to wait for a hearing — which could have resulted in jail time — while finishing her senior year of high school and applying for college. The family paid for counseling, hoping to help her work through her anger over the incident.

Eventually, the charges were dropped.

“It was like they didn’t want to see them succeed,” Stacy Walker said.

The school district said it could not comment on individual cases.

But in an interview this past spring, Hinds County Sheriff Victor Mason called on school officials to make “fewer arrests” and urged them to work more cooperatively with parents when students have discipline issues.

“I think we should be the last people called in,” he said.

Production and design by Alissa Scheller and Adam Hooper. Data reporting by Adam Hooper.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

Unlike most of our stories, this piece is an exclusive collaboration and may not be republished.