For millions of students, this is a summer like no other in the history of American public education. The last day of the school year was followed by just a brief pause before classes started again for a wide range of programs financed by more than a billion dollars in federal funds under the American Rescue Plan. That windfall sent educators scrambling this spring to find the best ways to spend it.

Many districts are trying to focus on students who have lost the most during months of remote learning. Educators say they are especially concerned about students living in poverty, English-language learners and students with disabilities. But kids of all ages — from kindergarten to high school — suffered academically and emotionally during months of isolation.

There’s no definitive count yet of how many students are enrolled this summer in a wide range of new options, from a push to close early learning gaps in Texas to a summer program in Oregon that helps kids learning English. A recent survey by the Center on Reinventing Public Education found that most large urban districts are offering an average of five weeks of summer learning, with many combining academics and activities like field trips or sports.

That’s the agenda in New York City, the nation’s largest district, where an estimated 200,000 students are enrolled in the Summer Rising program, a joint effort by the Department of Education, the Department of Youth & Community Development and community nonprofits. Like many programs, Summer Rising had a rocky start, with some administrators struggling to find staff and parents complaining about the sign-up process. But as classes started in early July, Rachael Gazdick, head of New York Edge, one of the participating nonprofits, said her focus was on the kids. “Our communities were hit hard,” she said, “and not every child is in the same place. We want to make sure they are absolutely supported.”

Here’s a look at how the summer is going for students around the country.

—Barbara Kantrowitz

Jump to a story

With millions to spend, districts try to help students recover from a difficult year

New York students get an extra dose of learning and fun

What English learners need most is to love school again

A push to close early learning gaps in Texas

Playing catch-up in districts that were already struggling

Summer programs are a lifeline for students with disabilities

With millions to spend, districts try to help students recover from a difficult year

SIMPSONVILLE, S.C. — About a dozen fourth and fifth grade students sat at scattered tables in Bethel Elementary School’s media center, trying to build bridges out of toothpicks and tape. Down the hall, students in small groups worked on reading and math.

It was the third week of summer school in Greenville County, the largest school district in South Carolina. Nearly 10,000 students who struggled this year were invited to attend the summer sessions, but the district estimates only about half showed up.

In a typical year, Greenville County does not have a districtwide summer school program except for a small camp required by state law for third graders who are not reading at grade level.

Flush with federal coronavirus aid dollars, about two-thirds of South Carolina school districts are using some of the funds to expand summer school this year, the state’s Department of Education estimates. South Carolina has received a total of about $3.3 billion in federal K-12 aid. Greenville County is spending $7 million of the funds on a summer program this year and another $7 million to replicate it next summer.

In Greenville County, students will spend four days a week for four weeks this summer on academics and hands-on activities. The district closed schools in March 2020 but started the 2020-21 school year allowing students to attend one day a week before gradually increasing in-person attendance. By the end of the school year, students who did not opt for full-time virtual learning were attending on a normal schedule.

Related: A new playbook for summer school

The goal of the program is to help students recover after a difficult year. More than 16,000 students in Greenville County Schools had at least one F on their fall report cards this year, or more than triple the number of students with Fs in fall of 2019.

At Bethel Elementary, just a few third graders — between three and five students — attended the county’s summer reading camps in past years. But 45 to 50 students are taking part in the current summer program.

Principal Matthew Critell said students who attended only virtual school this year are coming to the program academically behind their in-person peers.

Students take an assessment at the beginning and end of summer to track their progress, but staff at the school are not planning to retain students based solely on their performance over the summer. “The research really goes against retention,” Critell said.

Moriah Mullen, a special education resource teacher who is leading the summer program at Bethel Elementary, said students do get a break with physical education during the day, but even those activities have a literacy component. She’s been surprised at how happy students have been to be at school, even over the summer.

“I thought they were going to come in and be all upset that they’re in summer school, but I think it’s really good for them,” Mullen said. “They’re not at home all day.”

—Ariel Gilreath

New York students get an extra dose of learning and fun

NEW YORK — Pink and purple posters adorn the third-floor hallway at University Neighborhood Middle School on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. They’re advertising the after-school and summer programs the school runs with Henry Street Settlement, a community organization.

Nearby is a gallery of photos taken of the summer program from pre-Covid years.

“Look at her!” said Idalia Roldan, laughing and shaking her head while looking at a girl in one of the photos. “Always with that sour face!”

Roldan, a program coordinator for Henry Street Settlement, can name every student in the photos and share their stories. Because she knows the students so well, she has built close relationships with them and their families. This summer, after a difficult year, those relationships will matter more than ever.

“We want kids to feel comfortable going to someone they can trust,” said Maribeliz Ferrer, assistant director of after-school and camp services at Henry Street Settlement, “and they all love Idalia!”

The middle school is one of three school sites where Henry Street is providing afternoon activities through the city’s Summer Rising program, which started on July 6 and has been serving an estimated 200,000 students from kindergarten to high school.

Summer Rising, run as a partnership among the Department of Education, the Department of Youth & Community Development and local community-based organizations, is attempting to replace traditional summer school this year — and perhaps permanently. Any student living in the city — the nation’s largest school district — was eligible to attend.

Related: Counting on summer school to catch kids up after a disrupted year

The program includes morning academics led by schools, followed by recreational activities in the afternoon, mostly run by community organizations like Henry Street.

Parents have criticized the rollout of the program, but the people who run the community organizations say it could still make a big difference. One of those groups, New York Edge, which has been organizing after-school and summer programs for over 25 years, is offering 103 summer programs this year, serving 12,000 to 15,000 students across the city. CEO Rachael Gazdick says New York Edge concentrated on providing a vast range of activities — arts and sports, chess and robotics, cooking and career readiness. A fair at the end of the program will highlight students’ achievements.

Aaron Cummings Jr., Henry Street’s director of child programming, hopes to get students “out and about” through outdoor activities like gardening and field trips. There will also be opportunities for kids to talk about what they have been through this year.

“Covid is still very much a reality in our community,” he said. “They’ll process Covid and what took place and realize that there are support systems out there for them — that there are people they can lean on.”

At the end of the summer, the community organizations will ask for feedback from families. “We want to make sure that we’ve made it easier for the families,” said Cummings. “I think that’s what success looks like for us this year. It’s making sure families and children feel comfortable again.”

—Juliana Giacone

What English learners need most is to love school again

OREGON CITY, Ore. — Aylin Garcia Rosas, 9, and her 8-year-old cousin were crouched on the floor in the gymnasium at Holcomb Elementary School chattering in Spanish about how to get a Lego figure to stay on the car they were building.

The cousins are two of the 465 students enrolled in a brand-new, free summer program for students entering kindergarten through eighth grade in Oregon City, about 30 minutes’ drive south of Portland.

“It’s not really summer school,” explained Finn McDonough, 7, as he worked on a color-by-number project after finishing breakfast, which is offered free to all students here. “It’s summer camp.”

Stephanie Phelps, a summer school administrator, laughed when she heard Finn’s assessment and explained that academic skills are integrated into every activity, even if the kids don’t notice. More than 50 percent of those enrolled in the six-week program are English-language learners; 13 of them, including Aylin and her cousin, are classified as migrant students, meaning their parents are migrant agricultural workers, and they get two additional hours of math and reading in the afternoon. When asked about the afternoon, Aylin echoed Finn, insisting the group just played games.

Having some fun at school after a particularly brutal year is going to be key to long-term academic success for English learners, said Patricia Gándara, a professor of education and co-director of the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Related: Opinion – Creating better post-pandemic education for English learners

“These kids have fallen behind more than other children,” Gándara said. “They need to be doing things with other children, talking with other children, and not being given worksheets to just remediate.”

Most English-learner students are the children of immigrants, a population that was hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic, Gándara said. Immigrant workers were more likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic, and many are front-line workers.

About 15 minutes north of Oregon City, 80 students at Lot Whitcomb Elementary, in the North Clackamas School District, are spending four weeks in a dual-language summer program, reading Spanish-language stories, practicing math skills and talking to each other — a lot.

Since online classes made it hard for students to converse, this summer “our push is to work on discourse,” said Jenica Beecher, the English language development specialist for the district, which serves around 17,000 students.

The dual-language summer program at Lot Whitcomb isn’t new, but enrollment doubled and the day lengthened by several hours in 2021, said summer principal Brittany López. Districtwide, North Clackamas is serving 3,700 students in several summer programs, more than twice its typical enrollment, according to a spokesperson.

Oregon invested $195.6 million in summer school grants this year, requiring that districts provide 25 percent of the total cost for their programs. Some districts used federal emergency relief funds to cover their portion.

Back at Holcomb, Aylin used a second rubber band to strap her plastic Lego figure more securely in place and hurried out to the test track set up in the hallway.

After she failed twice to get the car through the step stool that was serving as a tunnel, her cousin, who arrived in Oregon City only a few months ago and still speaks little English, took over. He lined the car up carefully at the top of the ramp and let go.

It sailed right through.

—Lillian Mongeau

A push to close early learning gaps in Texas

COLLEGE STATION, Texas — On a Wednesday morning in late June, 12 kids were scattered around Rebecca Young’s classroom, tucked away in the back of River Bend Elementary on one of the last days of a new intensive summer school program. Four children sat across a table from Young, with whiteboards positioned in front of them and markers in their hands.

The word “fit” was written on each board. “Who can change the word ‘fit’ to ‘bit’?” Young asked, slowly enunciating each word. “Buh, buh,” one child said out loud, trying to figure out which letter he needed to write. One by one, each child erased the “f” on the whiteboard and wrote a “b.”

“Which sound is different?” Young asked.

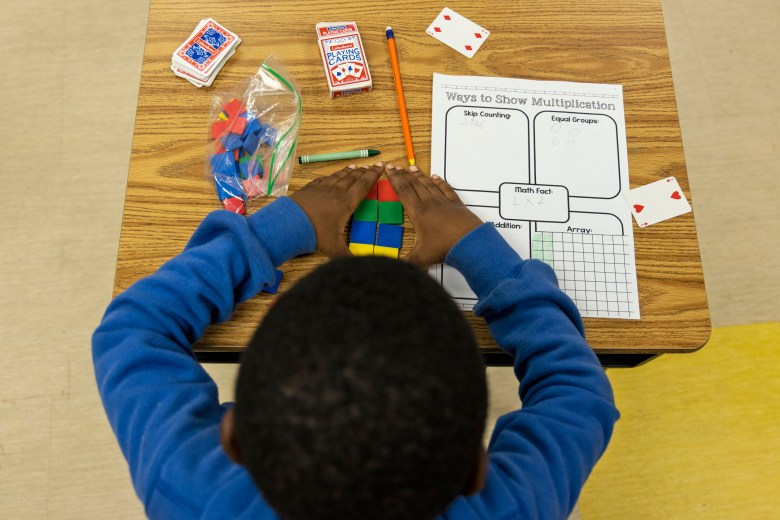

While Young led the small group of rising first graders through more practice with phonics, four other students were sitting at desks, playing a math game on their iPads. Two students sat in the corner practicing writing sentences, while a third sat on the ground with a colorful worksheet, identifying pictures and words with the digraph “th.” Another student was walking around the room with a clipboard, immersed in a “letter search.”

While this type of individualized learning would normally take up just a small part of a typical school day, it is the whole day in College Station Independent School District’s summer school program. The program was designed after educators and administrators in this East Texas district saw gaps emerging in elementary students’ reading and math scores last fall.

Although the district opened for in-person classes last August, some students stayed home and opted for online learning, and others were interrupted by random periods of quarantine due to exposure to the coronavirus, said Penny Tramel, chief academic officer. Tramel and her team, who in many prior years had never offered summer school, realized an intensive array of summer offerings was the best way to try to catch kids up on foundational skills in reading and math.

Related: How one district went all-in on a tutoring program to catch kids up

Almost immediately after school ended in late May, the district launched a four-week summer program, funded with federal money, which targeted students who needed the most help with math and reading skills to move to the next grade level. For four hours a day, five days a week, classes capped at 12 students met for intensive lessons at three elementary schools, cycling through small-group time with a teacher and independent work targeting learning needs.

To lighten the load for teachers, the district created the curriculum and provided lesson plans and materials, including everything needed for each student’s independent activities. The district plans to follow up with a two-week camp before school begins in mid-August that will help jump-start the year for the lowest-performing students, and educators say they hope the program becomes a staple beyond the pandemic.

“I think that Covid has really highlighted the need for programs like this in general,” said Heather Sherman, assistant principal of River Bend Elementary and principal of the summer school program. “Even without the pandemic, there’s always that need for continual learning to prevent the regression that occurs.”

—Jackie Mader

Playing catch-up in districts that were already struggling

BELZONI, Miss. — Nechia Coleman noticed 8-year-old Donylen Bullock staring down at two neatly arranged rows of tiles. He had organized them by color, and she noticed he lacked enough pieces to keep the pattern going. Coleman, a veteran educator at Ida Greene Elementary in the Mississippi Delta, brought over a jar and scooped out a few more.

Moments like this were what Donylen longed for during the past year he spent learning remotely.

His mother, Jelisia Neal, had her eye on the year ahead when she enrolled Donylen in the five-week summer school session, where he would have at least an hour of reading instruction each day starting in June.

Sometime next spring, Donylen, along with thousands of third graders in Mississippi, may be required to take a mandatory reading test that will widely determine whether they’re allowed to move up to fourth grade. More than one-fifth of third graders at Ida Greene were held back at the end of the 2018-2019 school year.

Other education statistics in Humphreys County are also alarming. Fewer than 20 percent of students in schools there were considered proficient in math or English language arts, according to data from the 2018-2019 school year.

State education officials took notice. For the past two years, the community’s schools and those in neighboring Yazoo County have been overseen by state-appointed superintendent Jermall Wright because of low academic performance. It could be years before Mississippi agrees there’s enough improvement to allow the county to run education locally again.

Before the pandemic, students who failed a course were the ones enrolled in summer school, but this year education leaders in Humphreys and Yazoo determined eligibility would not rest on report cards. A fourth grader reading on a third- or second-grade level would be asked to enroll — regardless of what grades they brought home. The district is financing the effort through federal Covid-19 relief funds allocated to school systems.

While projections vary on how the pandemic has affected educational progress, researchers have consistently found that Black and Hispanic children and kids living in poverty are more vulnerable to falling behind.

Nearly all the children attending Ida Greene are Black. And many families in the area — where 37 percent of residents live below the poverty line — suffered financial hardships before Covid-19 devastated the Mississippi Delta.

“For us, our kids didn’t suffer learning loss necessarily because of the pandemic,” Wright said. “They’ve been suffering learning loss for a while, for a number of reasons. All the pandemic really did was to show us not just how far our students were behind, but exactly how far behind we were in terms of being prepared to meet their needs.”

While Donylen made the principal’s honors list, the 8-year-old has asthma and his mother felt more at ease with virtual learning during the school year. He seemed to follow along OK. But Neal would review his classwork and see questions he skipped over.

“We’re playing catch-up,” she said.

While Donylen liked the lunch his mom made and his online art class, he felt like it took more of an effort to get Coleman’s attention. He had never met her in-person, but she seemed nice. If one of his classmates needed a crayon, she would produce one. He wanted that, too.

And for a few weeks, Donylen had it.

“I like that I can meet new people and can finally see Ms. Coleman in person,” he said, “and I like math.”

—Bracey Harris

Summer programs are a lifeline for students with disabilities

Danielle Eddins spent more than a decade as a preschool teacher, but nothing had prepared her for the experience of overseeing the education of two of her sons this past year. Her 6-year-old, who has autism and an intellectual disability, lost interest in what was happening on his laptop screen almost as soon as she powered on the device each morning.

“He would be staring at the computer, but there was no cognitive connection, no understanding that, ‘Hey, I’m in school,’” she said. Her 4-year-old, who has a speech delay, had trouble paying attention, too.

The boys’ sessions with teachers and therapists often overlapped, and Eddins struggled to manage them while also caring for her 19-month-old son.

Soon Eddins, whose older children attend Boston Public Schools, noticed changes in her oldest boy. He stopped responding to physical gestures, lost the few words he’d started to say and grew moodier and more frustrated.

Then Eddins learned her boys had qualified for “extended school year,” a federally mandated summer program for eligible students with disabilities. This year, unlike last, the program would take place in person. Eddins was encouraged, particularly for her oldest son.

“It’s important for kids to get that social interaction, especially having autism,” she said. “I need him to be socialized around kids his own age, even if he doesn’t play with them.”

Around the country, many parents of students with disabilities are counting on summer learning to help their kids recover skills they lost during the pandemic. These students often found remote education particularly challenging and in some cases went without services such as occupational and physical therapies and the socialization that comes from school.

Related: Is the pandemic our chance to reimagine education for students with disabilities?

But while some districts are stepping up their summer offerings to kids with disabilities, others are struggling to effectively serve these students amid staffing shortages and other challenges.

“The biggest problem that we’re seeing right now across the board, which is not specific to students with disabilities, is who is actually going to run these summer programs,” said Valerie Williams, director of government relations for the National Association of State Directors of Special Education. “Teachers are completely wiped out and burned out from everything they’ve had to manage and juggle for the past year.”

Some districts have delayed summer school for kids with disabilities. Others have reduced the number of kids served. Still others are struggling to accommodate kids with less severe disabilities, who don’t qualify for extended school year programs, in general summer offerings.

“Instances I see where students are being offered more than what they had last year, or more than what they had pre-Covid, are very rare,” said Cynthia Moore, founder of Advocate Tip of the Day, which supports families of kids with disabilities in Massachusetts.

Eddins considered herself lucky that her sons qualified for five weeks of extended school year programming. But she wasn’t leaving anything to chance. On their first day, July 12, she sent them on the bus with printouts of their Individualized Education Programs, personalized learning plans for students with disabilities. She called the school multiple times to check in. Over FaceTime, her 4-year-old’s teacher showed him playing with other kids. “He made friends right away,” she said. Her 6-year-old did well, too.

“So far, so good,” Eddins said. “I am hopeful that this summer will be good for both my boys. … I am not going to survive, not one more remote situation. It was so difficult.”

—Caroline Preston

This story about summer school was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.